Santosh Yadav, a migrant labourer working in Delhi, visits a retail store every week to send money to his family back home. Like Yadav, millions of people in India's cities still rely on retail outlets for such financial transactions. For all the hype around digitisation and mobile payments boom, a huge segment of India's population still sees cash as king.

And that's exactly the sprawling customer base Gurgaon-based fin-tech firm Eko India Financial Services Pvt. Ltd is looking to target.

Today, 80% of Indians continue to earn in cash and are mostly unbanked, says Eko's co-founder Abhinav Sinha. "We saw a huge potential in domestic remittance, and targeted immigrant workers in India's urban areas who want to send money back home," he adds.

Eko’s target customers are low- to middle-income people, earning Rs 10,000-50,000 per month in cash. "This segment earlier sent money through post offices, hawala, or bank branches. We decided to build a model where a customer could walk in to our retail partner outlet and remit the money instantly using a mobile phone," Sinha explains.

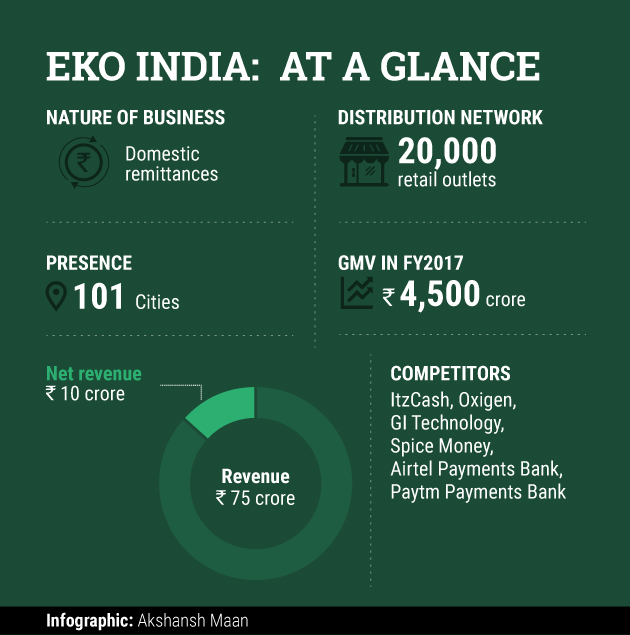

As of today, Eko's network covers 20,000 outlets across 101 cities. However, the chunk of its business is concentrated in urban India, including Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Lucknow, Kanpur and Jaipur since these cities top the domestic remittance list. In the financial year 2016-17, Eko processed remittances worth around Rs 4,500 crore, clocking 82% year-on-year growth. Currently, it remits close to Rs 700 crore a month.

Fund crunch

Despite having made inroads into India's still-strong cash economy, the company has been struggling for funds.

It last raised $5.5 million in 2011 from Chicago-based Creation Investments Social Ventures Fund I, Promus Equity Partners and a consortium of high-net-worth individuals. A year earlier, it had raised funding from US-based 4B Capital Fund A and received a grant from CGAP Technology Program, which is co-funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Despite the backing of big names, Eko's funding plans seem to have gone awry. And that can be limiting for a business that's looking to expand by on-boarding and training retail outlets.

Sinha feels part of the blame lies with Eko's initial business correspondent model.

Forgettable start

Eko started operations in 2007 as a business correspondent for banks. It collaborated with banks and retailers, and opened bank accounts and enabled deposits/withdrawals for customers at retail stores. When a customer walked into an Eko retail store, he would be asked to furnish address and identity proofs, and the firm would open an account for him instantly. From 2008 to 2011, it partnered with leading lenders such as State Bank of India, Yes Bank, and ICICI Bank, functioning as a business correspondent. But the founders soon realised that it was difficult to work with traditional banks, and pivoted to become an independent remittance company.

"From 2007 to 2015, we were doing business correspondent work...a space that has been very toxic. We were putting the same amount of effort with banks, but not able to scale up as traditional banks operate differently. No business correspondent has gone ahead and raised significant funding as none of them is big enough, except FINO PayTech. And that's because Fino started off as a venture incubated within ICICI Bank, and 14 banks were its shareholders," Sinha claims.

By the time the realisation happened, the company had missed early opportunities in the digital payments space, with the likes of Paytm and MobiKwik already having captured the lion's share of the market.

"It took us lot of time to close the business correspondent business. By that time, we saw that wallets were scaling much faster, mainly because banks did not have an overbearing influence on them," Sinha recalls.

Eko received the licence for its pre-paid wallet in March 2015, and it became operational in August. And it decided to offer a wallet solution for domestic money transfers.

Business and traction

Eko, which runs a two-tier network involving distributors and retailers, charges its customers 1.5% commission. Of that, the distributor and retailer pocket close to 1.2%. The rest 0.3% comes to Eko. Last year, it posted a top line of Rs 75 crore, of which around Rs 65 crore went to distributors and retailers. Eko's net revenue was Rs 10 crore.

"As far as payments businesses, such as remittances or gateways, are concerned, they make a net margin of 0.2-0.3%. Having broken even, and with just 68 employees, we are an efficient company...among the top two remittance companies in India outside banks," Sinha claims.

"Initially, we were doing Rs 120 crore in annual gross merchandise volume (GMV), and today it stands at Rs 700 crore. We scaled up to six times in the past two years," he says.

Eko, which has started international inward remittances from Nepal and looking to tap other countries, is eyeing Rs 10,000 crore in GMV in the coming financial year.

Competition

Eko competes with the likes of ItzCash which recently got acquired by US-based Ebix for $120 million, Oxigen, GI Technology, Airtel Payments Bank and Paytm Payments Bank.

"Despite having larger teams and bigger networks, some players have not been able to crack this space. Whoever executes better, wins. We know the cash business better than the online guys," says a confident Sinha.

As for competition with Paytm, Sinha feels the Vijay Shekhar Sharma-led unicorn and Eko serve a completely different set of customers, and the challenges in offline are far greater. "Unlike the online world, offline play is not so easy...Going to a retail merchant to buy bread, or to load cash/transfer money are different cases. The reason offline payment companies are not able to scale as fast as online rivals is that we have to set up a distributor and retailer network and also train them. It's a different ballgame altogether."

Sinha acknowledges that Paytm has the potential to disrupt the market. At the same time, he feels the entry of Amazon into the wallet space will distract Paytm, and "under pressure to protect its turf, it will not do a good job in Eko's space hopefully."

As of 2016, India's domestic remittance market was doing merely Rs 4,000 crore a month, which is a fraction of what developing countries like Kenya and Bangladesh clock. Kenya sees thousands of crores (in Indian rupees terms) getting transacted every day while the corresponding figure for Bangladesh is close to Rs 700 crore. Vodafone M-pesa and Bkash are the largest players in Kenya and Bangladesh, respectively.

Too early in the game?

Sinha does believe Eko entered the space a few years too early: "We were before time and it was not a good decision. As entrepreneurs, we were not right in choosing the right product-market fit."

He cites the example of Snapdeal's Kunal Bahl, who admitted in a letter to employees that the founders "started growing business much before the right economic model and market fit was figured out."

"Despite the fall in valuation, Bahl is sitting on $1-billion dollar company and still saying e-commerce came before the market fit. We have gone through that pain ourselves in terms of size and funding," Sinha says.

But, aside from the the fact that Eko is a lean, efficient company, there are other green shoots. Take, for instance, the way it has bounced back after the onslaught of demonetisation. Before the government's November move to ban old high-value notes, it was doing close to Rs 500 crore in monthly GMV, with 1.5-2 million people remitting through the company. "Our business shrank by 50% at that time. However, around the third week of December, as cash started coming back to the system, business was slowly back on the track. In March, we did more business than pre-demonetisation levels," Sinha says smilingly.

"I won’t say cash is going to be there forever, but in a country like India, things are not going to change overnight," he signs off.

It's tough to contest that argument.