Corporate titans leading Australia’s top 50 companies are as likely to have degrees in engineering as commerce or economics, a LeadingCompany analysis has found. And, it’s not just Australian mining conglomerates where engineers are rising to the top. Around the world, a combination of sound engineering acumen with an MBA from a top business school tends to be a common path to the corner office. Microsoft CEO, Satya Nadella, is an engineer. So is General Motors’ Mary Barra and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos; and the list goes on. In fact, engineering has long been ranked as the most common undergraduate degree among Fortune 500 CEOs. Even Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, has an engineering PhD under his belt.

Why do engineers end up leading companies? Is it because engineers – at face value – are CEO material, or because they are more likely to have changes of heart during their career? If so, why, how and when does this occur?

Image problems

In spite of engineering’s long and glorious history – think Thomas Edison, John Frank Stevens, Henry Ford, and Herbert Hoover – there seems to have been stereotypical image problems associated with the profession. While it’s true engineers have often been identified as technical geeks, who excel at maths and physics, many also exude a host of socially-acceptable traits that eventually earn them the awe of their boards of directors.

Engineers, in general, are found to be good at attention to detail, problem-solving, numeracy, risk management and analysis.

On the flip side, many may lack emotional intelligence and the necessary leadership, people management, and communication abilities – soft skills which can be addressed by training to assist their transition into the management arena.

Grass is greener

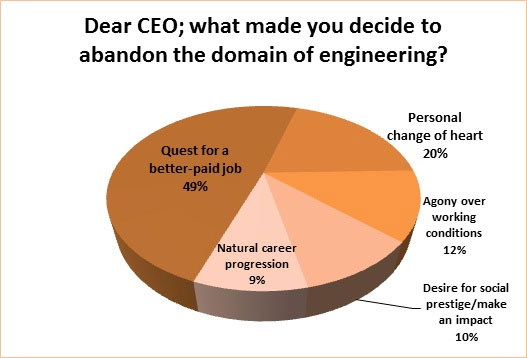

So what motivates engineers to depart from their more-technically-oriented career paths and make their way to the boardroom? Of the 300+ responses to an online survey I conducted with 1,280 top-level executives holding engineering degrees, the overwhelming reason for moving up was money.

Despite engineering being one of the more financially-rewarding professions, many of the engineers-turned-CEOs surveyed noted that lawyers and bankers make vast multiples of what engineers do. We live in a world where the monetary value of professionals does not always correlate with the magnitude of value created for society (it can be argued that nurses, teachers and NGOs are important value creators; yet they make very little compared to, say, investment bankers) and high pay seems to rank very highly as a motivation for pursuing a management position. As Rita Davenport once said, “Money is not everything, but it ranks up there with oxygenâ€.

A safe start

Another group of engineers said their focus changed after realising a traditional engineering job no longer satisfied the desires that originally led them to pursue that career path. In fact, some discovered they had never held a genuine desire to be an engineer in the first place. The prevailing wisdom in many parts of the world, especially developing ones, is that high-achieving students are expected to enrol in either medical or engineering schools. There seems to be a widespread assumption that taking on medical or engineering studies is far more difficult than studying the humanities and social science disciplines. Some of the surveyed executives admitted that since engineers enjoy one of the lowest unemployment rates, engineering has always been perceived as a safe starting major for anyone, providing graduates with a set of skills that cannot be faked and which open doors for professional advancement.

Other recorded reasons for pursuing leadership positions included disillusionment with harsh working conditions for engineers (the life of an engineer, it seems, is not as rosy as originally anticipated), while for others, it was not so much a wrong career choice, but rather a mere change of interest from a curiosity-driven fascination with how things work to a desire to make a difference or to acquire self-esteem.

“Their way†and the “wrong wayâ€

One of the counter-intuitive findings of this survey was that most CEOs do not reach their position as part of natural career progression, but rather through actively pursuing a management role. The reality is engineers are often promoted on the basis of their engineering accomplishments and technical merits, rather than their management abilities. One of the oft-neglected complications of such practices is that engineers have the tendency to think there is “their way†and “the other (wrong) wayâ€. In effect, this explains why engineers-turned-CEOs have a tendency to be ineffective delegators who adopt a micro-management style.

While many career changes are spurred by a perception that ‘the grass is greener on the other side', most career transitions boil down to individual preferences and market conditions. These appear to be strongly geographically-dependent, sector-specific and gender-oriented.

Additionally, the length of time spent in a technical role is expected to vary from one CEO to another. And once an engineer moves into the realms of the executive, it is highly unlikely they will return to a more practical role.

But, not all engineers are cut out to be executives. Many bright engineers develop no interest whatsoever in attaining a leadership position. This is not necessarily a bad thing given the high proportion of corporate psychopaths in the C-Suite. Mainstream engineers’ characteristics, it appears, don’t figure highly in the spectrum of psychopathic tendencies. Until they become CEOs at least.

(Yasser Al-Saleh is a Senior Research Fellow at INSEAD Innovation and Policy Initiative. He comes from an engineering background and has previously worked in the oil industry.)

To become a guest contributor with VCCircle, write to shrija@vccircle.com.