“Bankruptcy law should provide a framework to permit viable but liquidity constrained firms (those which can be reasonably expected to earn at least their cost of capital if continued but which are presently unable to meet their financial obligations) to reorganize and continue doing business and non-viable firms to be liquidated”: Professor Kevin Kaiser in his book on Corporate restructuring (1996).

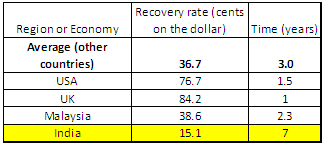

As per the Doing business (An IFC feature) report’s data, the average recovery rate on defaulted debt in India is 15.1% which is almost half of the global average. The average time taken to close down a defaulted business down is 7 years compared the global average of 3 years. Obviously, the Indian bankruptcy code has not been able to differentiate very well between the viable and non-viable businesses in India. Our system of restructuring / resolving distressed debt cannot qualify as one of the most efficient worldwide.

The process for resolution of debt in India has been fraught with certain attributes that lead to long delays and provide the debtor a safe haven for several years despite poor performance. This article attempts at understanding the reasons for these poor recoveries and longer recovery periods.

BIFR: Safe haven for debtors: Liquidation is a rare event in Indian proceedings!

Schemes of reorganization of distressed debt can broadly be classified into two broad models:

• One which has a greater focus on rapidly securing creditor’s claims with slight weight given to keeping a firm in business (UK , Malaysia)

• The other that focuses more on maintaining firms as going concerns and gradually satisfying the rescheduled claims of the creditors (USA, India)

Source: Doing Business data, International Finance Corporation

As per the data above, the average recovery rate of distressed debt in UK is better than that of USA and also the time to close a defaulted business is lowest among all the countries. There are reasons for this in the way the bankruptcy proceedings happen in UK. The UK insolvency act of 1986 which is the basis for the British bankruptcy proceedings has a heavy bias towards liquidations over rehabilitation. The process makes it more liquidation friendly than re-organization. The secured creditor appoints a receiver who will look to dispose off the assets of the debtor if the debtor can manage to turn around the company with limited efforts.

At times, an administrator receiver is also appointed by the secured creditor who has powers of reorganization but is handicapped due to the pressure from the creditor to recover its claim as soon as possible. The court has the power to appoint a third party administrator who has powers to rehabilitate the firm as a going concern but this power is limited by the fact that the administrator can only be appointed if there were no receivers appointed by the secured creditors in the first place. In most cases, the secured creditor would place a receiver at the earliest and try to rule out the appointment of an administrator by the court.

A similar success story from the creditor stand point has been in Malaysia. In 1998, the government in Malaysia initiated an Asset management company called Danaharta due to the looming crisis the economy was facing. Danaharta has been relatively successful in the region and under the structure corporate bankruptcy recovery rate has been better than its south east Asian counterparts. Permission to foreclose on assets without reference to the court and also considerable influence over the restructuring process through administrators has helped Malaysia bring their recoveries up in comparison to India.

In India, the SRFAESI act was expected to provide a similar solution where the creditors could enforce security interests without court intervention. Unfortunately from the creditor stand point, it did not pan out in a similar fashion as in Malaysia. There have been instances in corporate bankruptcy cases in India where despite the enforcement of SRFAESI by creditors, the court intervened and found a loop hole in the act to protect the liquidation of debtors assets. The act still needs to be looked into to provide the creditors with that sort of power.

Rehabilitation of bad firms in bad situations still remains a problem in India and BIFR continues to provide the debtor a safe haven despite the SRFAESI act introduction.

Bankruptcy Definition in BIFR

The saying “Prevention better than cure” holds true in bankruptcy proceedings as well. In BIFR, the debtor becomes eligible to file for bankruptcy only when the accumulated losses override the net worth of the company. This enabled the firms to enter BIFR at its last breath when the company had totally eroded its net worth. They come into BIFR when it is on a deathbed. Hence the liquidation value of the company suffers which leaves the equity with almost nothing if there is a liquidation sale. This provides a greater incentive for the promoters to push for Debtor in possession reorganization rather than liquidation and in process extracting value from the company.

Under Chapter 11, the reorganization procedure for US bankruptcy cases, a debtor can anticipate insolvency and hence file for bankruptcy way before the situation worsens. UK Insolvency laws follow what they call as cash flow insolvency method where it considers both : whether current debts are unable to be paid when it falls due and also whether future debts will not be able to be paid. This makes it possible for creditors to call for insolvency earlier.

The Indian definition for entering BIFR needs to be amended to detect bankruptcy at an early stage in order to have a meaningful attempt at rehabilitation of the company.

Employee Power in the process

Trade unions and employees have a lot of say in the bankruptcy resolution process of BIFR rehabilitation. In India, workmen's dues have a dominating preferential claim to all other type of claims be it debt or equity. Strength of workers and employees in the BIFR process ensures that even non-viable companies give a shot to rehabilitation.In some countries such as US and UK the rule places the secured creditors before the employee claims and it is the reverse in India, Brazil where the employees have the first right to get their claims satiated.

Employee’s fear of losing his source of livelihood has traditionally kept the employees to be in favour of the promoter/management’s interests to rehabilitate even an unviable firm instead of liquidation. Despite their high status in the liquidation claim in India, the employees have traditionally been seen to side with the management to keep the firm as a going concern.

The average time to close down a defaulted business in economies where creditor claims over rule the labour claims is around 1.5 years in comparison to 4 years it takes in economies where the labour claims come before creditor claims.

Consent from all stakeholders to approve the reorganization plan takes time

The reorganization plan unlike in Chapter 11 requires consent of all the claimants involved in the process. Hence it takes much longer to convince every claimant on board in the process.

Under Chapter 11, for a class of claims (i.e. creditors) to approve the plan, at least 50% in number and at least 2/3rd in dollar amount of the voting creditors need to vote in favour of the plan.

• Classes that receive a 100% recovery are called “unimpaired” and are automatically deemed to accept the plan

• A creditor committee is formed out of the impaired classes who do not get a 100% recovery and are the main voters for the plan.

• Provision for a Cram Down procedure: If the judge finds that the plan is fair to all claimants as per the priority rule and is in good faith, but gets rejected by a particular claimant class for non-justified reasons, the judge can exert his power to approve the plan and hence cram down on the plan.

Availability of the cram down provision and majority voting acceptance are the salient points of the US bankruptcy code for faster approval of a reorganization plan. The current Indian laws lack such optionality .

Biggest creditor head of the restructuring panel led to the overinvestment problems

Historically, the operating agency (‘OA’) under BIFR had been the creditor with the largest exposure. This would lead to the classical “over-investment” problem. The creditor would want maximum recovery for his claim and in most cases find that the liquidation value of the firm is drastically lower than his claim. They would repeatedly approve of plans that call for further investments in the hope that the firm restructures and the creditor could realize a greater chunk of value.

Under Chapter 11, a creditors’ committee is formed which normally includes 7 of the top 20 largest unsecured creditors (due to their impaired status). The committee consults with the debtor on administration of the case; investigates the debtor's conduct and operations; and participates in formulating a plan.

As the larger creditor is moved out of the voting decision, the creditor committee solves the over investment problem to a large extent in the US bankruptcy scenario.

Has Debt been an effective policing mechanism for corporate performance in India?

The static trade off theory of debt provides for the reasons why companies lever up and add debt to their capital structure. The most important reason of course is the interest tax shields that the companies get on account of debt. The interest tax shields have an enhancing effect on the value of the levered company. At the same time, there are costs of bankruptcy attached to undertaking debt that start offsetting the additive value of the interest tax shields as the debt increases in a firm.

In India, the debtor is bound to perceive the indirect costs of bankruptcy to be less significant than debtors in US and UK due to the safe haven they get even after defaulting on debt commitments. An un-viable business is also given a long time to be run as a going concern. An average period of seven years after reporting distress to close a company is a long enough period for a debtor to take advantage of the information asymmetry and hence violate the APR to make gains for itself by jeopardizing the claims of its debt holders. The management hence might not perceive the costs of distress to be too high and take decisions that will shift the optimal debt ratio towards more leverage. The incentive for the management to increase the debt in the company will displace the optimal debt potential of the company.

The other advantage of debt is that it brings in ex-ante discipline in the management of companies. Given the leniency towards debtors in bankruptcy proceedings in India, the question is whether debt really is an effective policing mechanism in India for corporate performance.

The setting up of NCLTs and the SRFAESI act were supposed to be the steps to empower Indian distressed debt recovery. Unfortunately, they have not been implemented effectively to change the status quo of the corporate default recoveries. The bankruptcy code in India needs to be effective in demarcating between viable and non-viable firms to aid the adoption of an effective resolution route.

( This is part of " The VCCircle classroom" series in alliance with The Indian School of Business, Hyderabad).