In the months since office-sharing startup WeWork's botched public debut, mid- and late-stage investors in big start-ups have been pushing for more safeguards in case their firms fail to go public or sell shares at a lower valuation than pre-IPO financing rounds.

Fundraising terms are rarely made public, but more than a dozen Silicon Valley-based lawyers, entrepreneurs and venture-capital investors told Reuters that since WeWork's canceled public offering and other ill-fated IPOs, investors have been securing protections of their original investments in "unicorns" - private companies valued at $1 billion or more.

Tougher terms are the price to pay for ensuring late-stage funding and sustaining the pipeline of initial public offerings, but also can be detrimental for founders, employees and early-stage investors, which in turn could make M&A deals challenging.

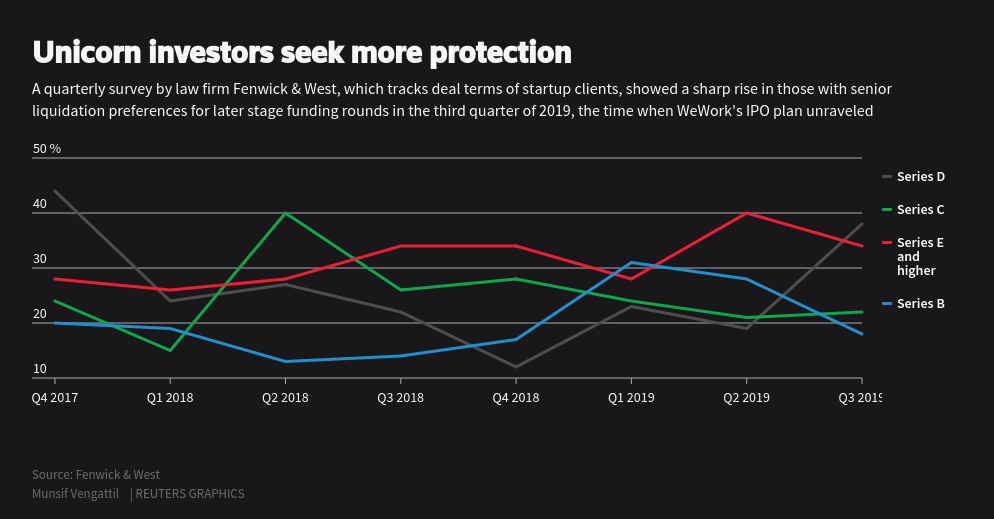

A quarterly survey by law firm Fenwick & West, which tracks deal terms of startup clients, showed a sharp rise in those with senior liquidation preferences for later stage funding rounds in the third quarter, the time when WeWork's IPO plan unraveled.

Safeguards include a higher minimum price on shares in an IPO, "ratchets" that give investors more shares if the shares are priced below what they paid, guarantees of a certain return on investments, and rights to block the IPO.

"Because many of these unicorn valuations are super high relative to historical IPO values, growth investors are putting in more structure around IPOs," said Ivan Gaviria, a partner at Gunderson Dettmer, a Silicon Valley law firm that works with venture-backed companies and investors.

WeWork's lofty $47 billion valuation tumbled to less than $8 billion after it scrapped its IPO in September amid a public shareholder-founder dispute that led to the founder-CEO's ousting and a bailout by SoftBank.

The Japanese technology conglomerate, which has invested in several high-profile tech start-ups including Uber Technologies, has been among late-stage investors especially forceful in demanding more safeguards in the event of a failed IPO.

Over the past four months, every SoftBank-led funding discussion for mid-to-late stage Internet startups has involved tougher terms for founders and employees, especially for commitments of $200 million to $300 million or more, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

For instance, in December when SoftBank was in relatively advanced talks to invest in pharmaceutical delivery startup Alto Pharmacy, the investment partners from its Vision Fund sought price protection clauses, as well as stronger corporate governance processes at the company, that person said.

SoftBank and Alto Pharmacy, which was previously known as ScriptDash, declined to comment.

First in line

An investor with a liquidation preference would get paid first when the company folds or is sold.

To be sure, some experts note that the push for greater safeguards preceded the WeWork debacle, but most lawyers and investors Reuters has interviewed said it has intensified after the WeWork flame-out.

Some investors are even asking to get back even more money than they put in, said Ed Zimmerman, partner at law firm Lowenstein Sandler, who represents tech companies and investors.

Sandy Miller, general partner at IVP, a later stage venture capital firm which is an investor in Uber, said many firms, including IVP, still prefer "clean term sheets" that put founders and all investors on equal footing.

However, an investor may want extra protection if founders push for higher valuations at a time when the market is leveling off.

"You may say, well, we can agree to a bit higher valuation, but we're going to need some terms around it."

Shawn Carolan, partner at Menlo Ventures, said investors have also been pushing for more say on certain matters. "It's mostly about compensation, indebtedness, major capital purchases or commitments, and major business agreements," said Carolan, who is the investment lead on Uber, among others.

Yet financial safeguards in particular can make it harder to make deals, especially when the company is sold rather than goes public, because once late-stage investors get their guaranteed cut, there might be not much left for anyone else.

"How do you buy a company with $400 million or $800 million of liquidation preference for under a billion dollars?" Zimmerman said. "And who can do that?”