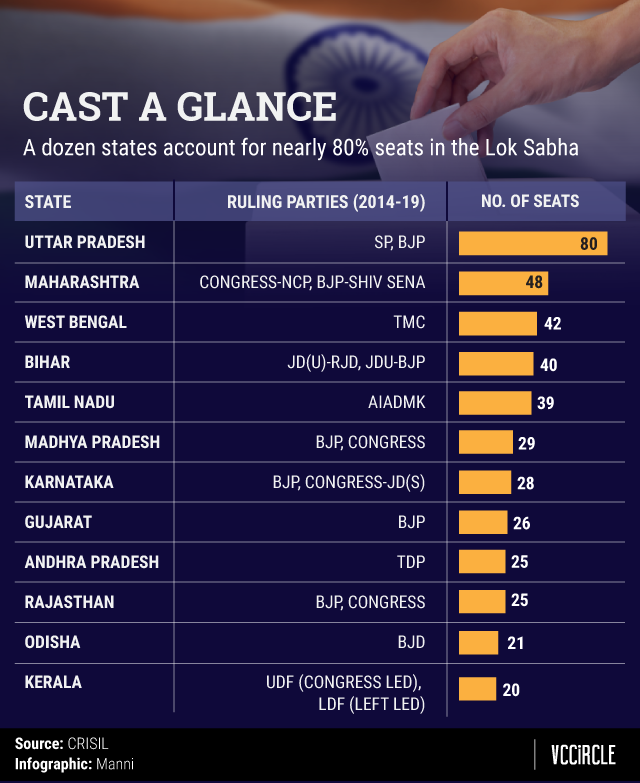

India goes to the polls on Thursday, with 142 million voters across 19 states and two union territories electing a fifth of the representatives that will constitute the next Lok Sabha. The Indian union is a sum of its federating units. In fact, psephologists often say that India’s general elections do not even have a pan-national character, but rather are fought state-by-state -- often over local issues.

As a whole, India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has averaged around 7% over the past five years, with the country emerging as one of the fastest-growing large economies in the world according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As Indian states vote over the next month to decide whether Narendra Modi will get a second term as prime minister, it’s worth examining how they have individually performed since his government has been in office at the Centre.

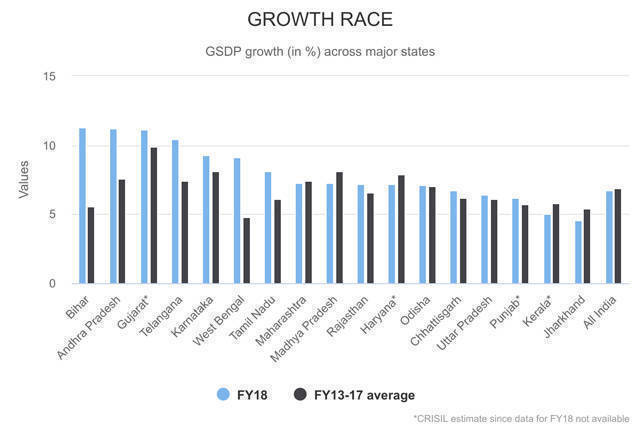

Traditionally better-developed states such as Gujarat and Karnataka continued to grow faster than the national average in the five financial years from 2012-13 to 2016-17, as per data compiled by rating agency Crisil that was released in January. (The Modi government has been in power since the second month of 2014-15.)

But in 2017-18, Bihar outpaced all the other Indian states by registering an 11.3% growth in its state GDP, even as the overall Indian economy grew by just 6.7%.

In fact, all but one of the so-called BIMARU states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) -- a term coined three decades ago to denote the poor growth of these states -- outpaced the national average of growth in 2017-18. This indicates the positive impact of business-friendly government policies and an improved law and order situation.

Incidentally, all of the BIMARU states have either been ruled by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or a government supported by it for at least two out of the last five years.

Another state which staged a surprise turnaround in 2017-18 was West Bengal, which has been ruled since 2011 by Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress, that is opposed to the BJP.

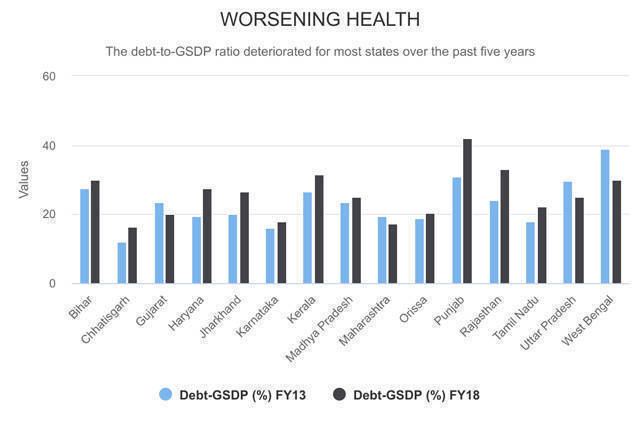

But growth rates aside, the financial health of nearly all India’s states worsened between 2012-13 and 2017-18, as their debt-to-GSDP ratios declined over the five-year period. GSDP stands for Gross State Domestic Product.

The data shows that among India’s 15 large states, only three -- West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra -- fared better on this count in the last five years for which data is available. The first two states were ruled by parties opposed to the BJP for the entire or major part of the period between 2013 and 2018.

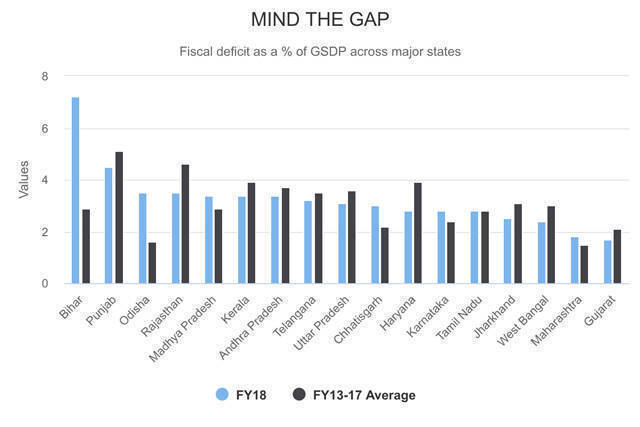

As their fiscal health worsened, most states were not able to adhere to the 3% limit on fiscal deficit set under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act of 2003. Figures show that in 2017-18, as many as 10 large states breached the FRBM limits.

One reason for this slippage could be that the states are simply spending more on capital expenditure than they were doing at the beginning of this decade. Crisil’s figures show that while in 2010, the central government’s share in capex in the economy was 67.4%, it had slipped to 51.3% in by 2017 before rising marginally in the following year.

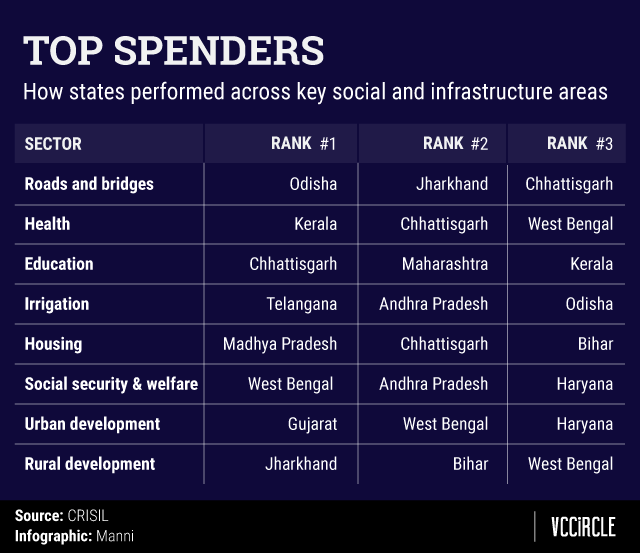

The Crisil report further shows that while the bigger states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Bihar, Karnataka and UP were the largest contributors to capex between 2014-15 and 2017-18, Haryana, Kerala, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh accounted for the least.

However, looked at individually, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, UP, Telangana and Bihar allocated the highest share of their respective budgets towards capex in the same period.

A sector-wise breakup of spends further shows that while almost every state made education its top priority with 16% or more of their expenditure being allocated for the purpose, housing figured near the bottom on their lists with 1% or less being spent on it. Health and education are other areas to which states have traditionally paid inadequate attention.