Persistently high inflation will haunt the world economy this year, according to a Reuters poll of economists who trimmed their global growth outlook on worries of slowing demand and the risk interest rates would rise faster than assumed so far.

This represents a sea change from just three months ago, when most economists were siding with central bankers in their then-prevalent view that a surge in inflation, driven in part by pandemic-related supply bottlenecks, would be transitory.

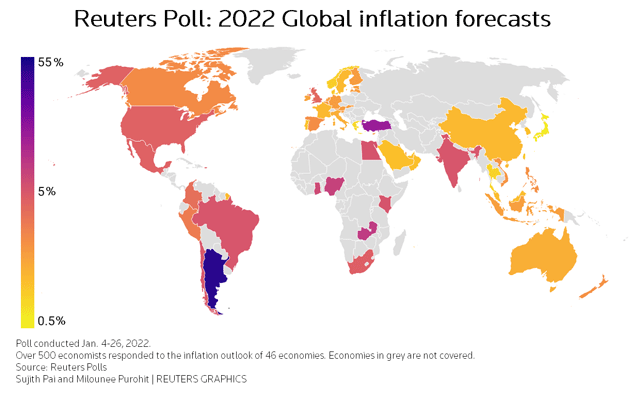

In the latest quarterly Reuters surveys of over 500 economists taken throughout January, economists raised their 2022 inflation forecasts for most of the 46 economies covered.

While price pressures are still expected to ease in 2023, the inflation outlook is much stickier than three months ago.

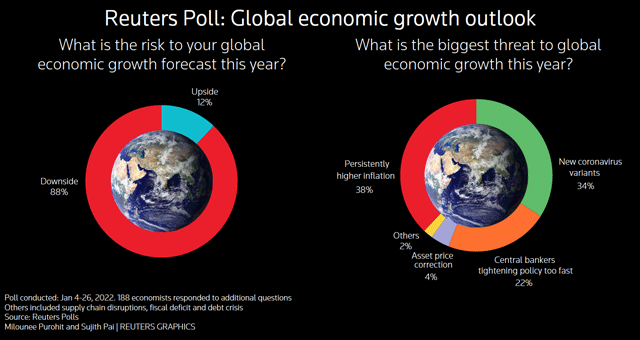

At the same time, economists downgraded their global growth forecasts. After expanding 5.8% last year, the world economy is expected to slow to 4.3% growth in 2022, down from 4.5% predicted in October, in part because of higher interest rates and costs of living. Growth is seen slowing further to 3.6% and 3.2% in 2023 and 2024, respectively.

Nearly 40% of those who answered an additional question singled out inflation as the top risk to the global economy this year, with nearly 35% picking coronavirus variants, and 22% worried about central banks moving too quickly.

"The odds of an accident have risen and the likelihood of a soft landing in 2022 requires some favourable assumptions and a modicum of good luck," Deutsche Bank group chief economist David Folkerts-Landau said, noting high inflation, the persistence of supply chain strains and the pandemic, as well as international political tensions.

This month's Reuters polls found 18 of 24 major central banks were expected to lift rates at least once this year, compared to 11 in the October poll.

The U.S. Federal Reserve on Wednesday signaled it would raise the benchmark federal funds rate from a record low of 0-0.25% in March after shuttering its bond purchase programme.

The Bank of England was the first major central bank to raise rates since the pandemic started and is expected to act again, the Bank of Canada is also seen hiking soon.

In contrast, most economists expect the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan to stay put at least until the end of next year.

While the tightening cycle is in early days in developed markets, many emerging market central banks, with a few notable exceptions like Brazil and China, are waiting for the Fed's cue while grappling with the pandemic and their own economic challenges.

"Over the past three decades, developed market central banks led by the Fed have been inclined to see supply shocks boosting inflation as a drag on growth that should be cushioned," noted Joseph Lupton, global economist at J.P. Morgan.

However, with major central banks showing concern about bringing inflation expectations close to their targets, emerging economies face a similar challenge.

"Pressure on emerging market central banks to act to anchor inflationary expectations is likely to intensify," Lupton said.

The growth outlook for over 60% of the 46 economies covered in the polls was either downgraded or left unchanged for 2022 and about 90% of respondents, 144 of 163, said there was a downside risk to their forecasts.

While most countries saw cuts in growth forecasts for the fourth quarter and the current one, largely due to the spread of the Omicron coronavirus variant, they were expected to rebound next quarter.

(For other stories from the Reuters global long-term economic outlook polls package)