When the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act (RERA) was implemented in May last year, it had ignited hopes among harried homebuyers burdened with investments sunk into delayed or stuck projects.

Until then, real estate was one of the only consumer-centric sectors in India that had remained largely unregulated, allowing unscrupulous developers to take middle or lower-middle-income homebuyers for granted.

A little more than a year later, has the new regulatory regime really been a boon for the homebuyer? Has it been satisfactorily implemented across the country? And does the new law need any more changes to make it better?

VCCircle spoke to real estate experts on how the first year of RERA panned out, and the picture that emerges is mixed.

A shrinking industry

Analysts say that RERA came about at a time when the real estate industry in India had been in a reset mode, after the November 2016 demonetisation in which high-value currency was banned, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime as well as the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC).

“All these regulatory issues hit the real estate industry,” says Vamshi Krishna Kanth Nakirekanti, executive director and head of valuation and advisory services at property consultancy firm CBRE Asia Pacific.

Ashutosh Limaye, head of research at consultancy JLL India, says while so-called ‘fly-by-night’ developers have been exiting since RERA was implemented, it would be unfair to think that all small players are unscrupulous. “It has nothing to do with the size or scale at which developers operate, it is about their intent. Several small players have made themselves RERA-compliant, because they want to be in this space for the long term,” Limaye says.

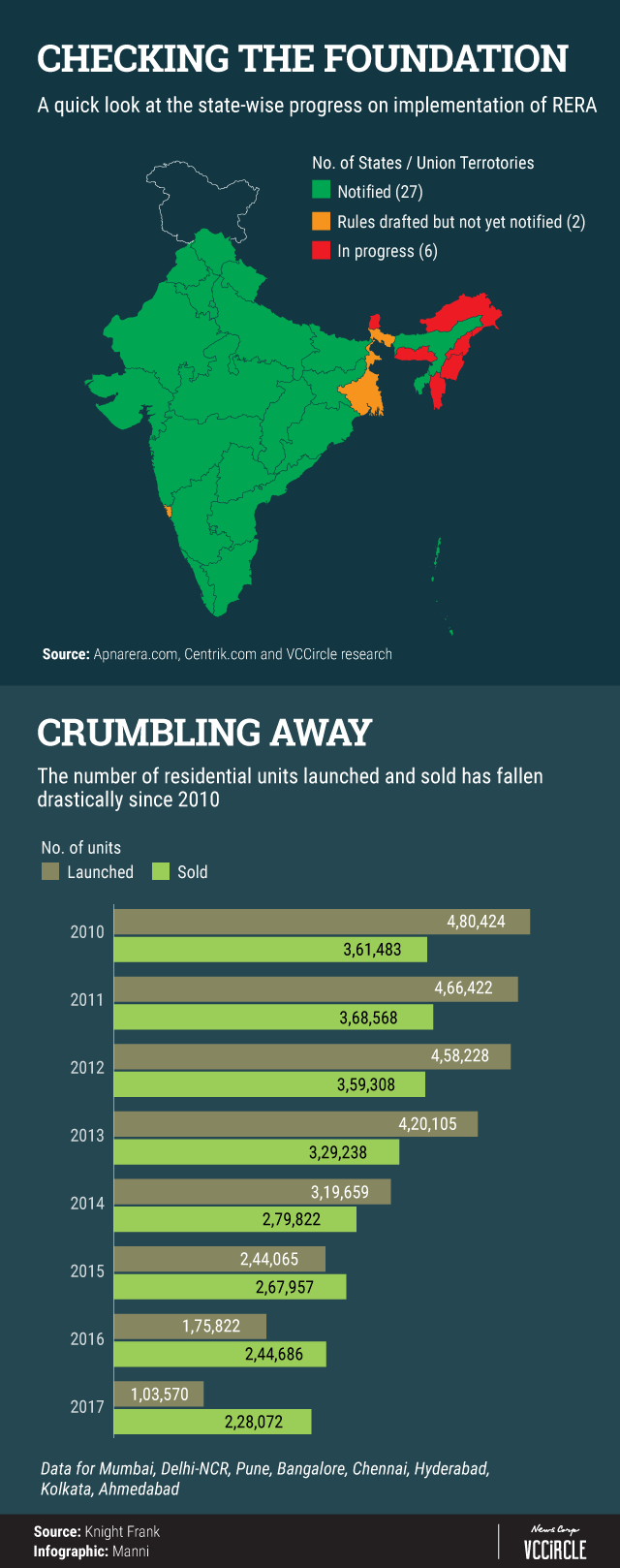

Analysts say RERA may have contributed to the overall decline in the number of launches but it hasn’t been the sole reason. The available data seems to support this claim. In fact, the number of launches and residential units delivered each year has recorded a secular decline since 2010.

Data available with real estate consultancy Knight Frank India shows the number of residential units launched across nine big urban agglomerations—Mumbai, Delhi-NCR, Pune, Bangalore, Chennai, Ahmedabad, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Ahmedabad—dropped from 4.8 lakh units in 2010 to just over a lakh in 2017. The number of units sold went down as well, from just over 3.6 lakh in 2010 to 2.28 lakh last year.

Vamshi Krishna of CBRE says developers have “not been shying away from new launches” but have rather been “redrafting their plans”.

“A lot of uncertainty exists in the developers’ minds as to how do they understand and implement it (RERA),” he adds.

Pankaj Kapoor, managing director at research firm Liases Foras, echoes this view. “Developers were laden with around 50 months of inventory, so they were in stress. But in the last two quarters, the flow of new supply has begun again, with the last quarter seeing a 72% increase in new launches over the previous quarter,” he says.

Kapoor debunks claims that RERA has shrunk the industry. “The biggest problem was among the large developers, who continue to exist. Smaller developers have not made much of a mess,” he adds.

Moreover, experts say the government’s moves toward bringing about affordable housing have actually broadened the market with newer players coming up in tier-II and tier-III cities. “The size of the industry will double in the next two years or so,” claims Kapoor.

Limaye agrees with this view and says the industry will expand as RERA has brought about a level-playing field. “It has defined the terms of business and professional practices. Everyone now has to be RERA-compliant. The differences between big and small players are vanishing, so more small players will come into real estate,” he adds.

Rebalancing the risk

Experts like Krishna say consumers have benefited from the implementation of RERA as the entire burden of risk of a project is now shared between the developer and the consumer. “Traditionally, the risk in most businesses is on entrepreneurs, lenders and equity investors. The consumer is not carrying the risk. But in the real estate industry, the risk got transferred to the consumer. With RERA and other regulations, the risk has now rebalanced and shifted from the customer back to the entrepreneur, where it should be,” says Krishna.

Moreover, the latest amendments to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), which put homebuyers on a par with financial creditors, are expected to help.

Under a new ordinance promulgated earlier this month to amend the IBC, homebuyers will be represented in the committee of creditors that decides on resolution plans, thus making them core to the decision-making process.

Kapoor claims that sales in Maharashtra over the past year have grown 25%, indicating that consumer confidence may be reviving. “This shows that there is rationalisation in prices, along with the coming of RERA, which has instilled a sense of confidence,” says Kapoor. “Moreover, there has been penal action in the recent past and several builders have been put behind bars,” he adds.

To be sure though, most cases of projects being delayed or completely going under happened with developers like Jaypee, Unitech, Supertech, DLF and Amrapali among others, who are primarily focussed on Delhi-NCR.

Limaye says before the implementation of RERA and the IBC, homebuyers had few redressal mechanisms, which led to a spate of protests. “The Maharashtra RERA, for instance, is progressively trying to settle disputes between developers and buyers, and facilitating one to one interactions or even via tribunals,” Limaye says. “Buyers, who earlier had no support, suddenly found a means to sort their grievances out, with RERA.”

Tardy implementation

Yet, issues remain. For one, not all states and union territories have actually implemented the new law yet and, therefore, do not have a regulator in place. As land is a state subject, each state has to implement the act and install a regulator separately. A VCCircle analysis shows that so far 27 states and union territories have notified the act, six had not yet done so, while two had drafted rules but not yet notified the act.

Northeastern states Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh seem to be particularly sluggish as none of them have notified the act.

Moreover, two states not ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—Kerala and West Bengal—have installed regulators of their own, which could even be in contravention of the RERA Act, says, Kapoor of Liases Foras. “West Bengal has come up with their own act—HIRA (Housing Industry Regulation Act). It is not a legitimate RERA,” he says. “Kerala came up with a website even before the RERA act was implemented.”

Kapoor says the issue of West Bengal and Kerala coming up with their own regulators even came up in a meeting of all stakeholders, chaired last month by union urban development minister Hardeep Singh Puri.

Similarly, although Delhi has notified the act, it has made the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) an interim regulator. This is a conflict of interest, as DDA is the state government’s main developer in the national capital.

Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat have diluted the provisions of RERA, says Kapoor. “Gujarat has come up with a provision that properties launched only after November 2017 will come under RERA,” says Kapoor.

Analysts say that one state that has implemented the act with gusto is Maharashtra. For one, experts like Kapoor say, this has happened because of the “passion” of the state’s RERA chief Gautam Chatterjee. “He has tried to bring in a situation where views of both the developers and the consumers were heard,” Kapoor says. Limaye adds that Maharashtra was the first state to have a dedicated website for RERA.

But the bigger reason for Maharashtra’s relative success with RERA perhaps is that it is one of the most urbanised states, and the disputes between the developers and consumers tend to be of a lesser degree.

Experts like Krishna say that with different states adopting RERA at different points in time, “a lot of uncertainty exists in the minds of the developers,” in terms of how they interpret, understand and implement it. “For example, how much money can be withdrawn from the separate account where they maintain all the cash flows, what proportion should they withdraw, was one question, everybody was trying to find answers to,” Krishna adds.

The RERA Act stipulates that, for project proceeds, a separate account be maintained and 60-70% of the money be kept aside for project expenses.

Fine-tuning the law

Experts like Kapoor say that sanctioning authorities should also come under the ambit of the new regulator. “It has made developers accountable, but delays often happen because of sanctioning authorities,” says Kapoor. “Unless you bring sanctioning authorities under the purview of RERA, the new law’s objective will not be met,” he adds.

Kapoor, in fact, says that a suggestion that has come up is that instead of government authorities or municipalities, professional experts such as architects and chartered accountants should be allowed to approve projects. “This will remove the monopoly of the government authority. But I don’t know how far this suggestion will go,” he says.

Further, since land is a state subject and the Centre has no direct jurisdiction over state laws, there is no chance for a central agency for RERA. Experts say there is a proposal to divide states up into zones and form regional councils, although nothing concrete has yet happened in this regard.

Talking of separate accounts, Limaye says the government “should look at introducing some flexibility” for projects in big cities where the land value is more than half the project cost.

“The assumption in the act was that 30% of the money would go toward land cost. But one year on, the government can define different grades of cities or zones within big cities based on the cost of land, and allow withdrawal of more money where land costs are high,” he says.