On 26 May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi completes four years as the head of India’s first majority government since 1984. While campaigning for the 2014 general elections, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had made a slew of promises to end the 10-year rule of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance. A corruption-free regime, 10 million new jobs a year and doubling farm incomes by 2022 were among those promises.

With less than a year to go before the next election, VCCircle takes a look at the Modi government’s four big achievements and failures during its tenure and four major opportunities it can still tap into.

Hits

Goods and Services Tax: Although the landmark legislation that overhauled the country’s indirect tax regime had been in the works for more than a decade and a half, the Modi government does deserve credit for getting the GST implemented in July 2017. However, the GST was not without its controversies that stretched India’s federal fabric to the hilt, resulting in strained centre-state relations at various junctures.

Moreover, what finally emerged was a complex multi-slab system instead of the one tax regime it was initially envisaged to be, even as key commodities like fuel and liquor remain outside the ambit of the GST. Further, owing to implementation glitches, tax numbers took a hit, at least in the initial few months following the GST rollout. Yet, the implementation of the GST did alter the country’s indirect tax regime for good.

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code: The Modi government can pat itself on the back for implementing a comprehensive bankruptcy law, India’s own version of the Chapter 11 regulation in the US Bankruptcy Code. Ever since its implementation in 2016 though, the IBC has been the subject of legislative and regulatory tinkering by parliament, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India and the Reserve Bank of India.

These encumbrances notwithstanding, available data analysed by BloombergQuint show that operational creditors have overwhelmingly outnumbered corporate debtors in using the provisions of the law—by as much as 87%—so much so that the latter are beginning to pay them even before they trigger the IBC.

Also in the news have been 12 large cases of defaulters as identified by the RBI. Just last week, debt-laden Bhushan Steel was acquired by Tata Steel for Rs 35,200 crore, making it the first big settlement under the IBC, with several other big deals set to close in the coming months.

No allegations of big-ticket corruption: The Manmohan Singh-led UPA was under fire during the last leg of its tenure as several of its ministers and members of parliament were embroiled in corruption cases. The Modi government can take some heart from the fact that no one among its top leadership or the cabinet has been accused of serious corruption thus far.

Rival political parties and some media reports have sought to target BJP leaders, but the charges haven’t really stuck enough for investigating agencies to get involved. Having said that, the Modi government has been accused of being in cahoots with some top industrial houses and going soft on high-profile defaulters like diamond merchants Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi and former liquor baron Vijay Mallya.

Aggressive foreign policy: In March, the Foreign Policy magazine reported that, until then, Modi had made 35 foreign trips as prime minister, having visited 53 countries, rubbing shoulders with nearly all of the world’s top leaders. Although Modi has been accused by foreign policy wonks of conflating action with achievement, he has succeeded in making significant rapprochement with key neighbors like China, evidenced by the amicable settlement of the Doklam standoff, which was threatening to snowball into a major armed skirmish.

However, Modi’s Pakistan policy and his overtures of peace, including an impromptu visit, have not paid off, as the Pakistani intelligence and army continue to back insurgent groups in the Kashmir valley. Moreover, the government’s trade policy, too, has seen average success at best, with the country actually reducing tariffs and ceding ground much beyond what the World Trade Organisation guidelines had demanded.

Misses

Make in India /Startup India: The Modi government had promised to make India a global manufacturing hub catering to both the export and domestic markets. The government followed through on this promise by launching its flagship ‘Make in India’ programme in a bid to significantly boost local manufacturing and creating a new skills development ministry to provide vocational training to unskilled youth. It also launched a much-hyped ‘Startup India’ programme with the ostensible goal of making India the startup capital of the world, just like Israel.

But none of these initiatives seem to have gone very far. In fact, how dismally India has done in export terms is borne out by the fact that the country’s trade deficit with China remains skewed in the latter’s favour by a ratio of four to one. According to a status report on the Startup India website, only 74 startups had been identified to receive tax benefits as of January first week.

Black money: On 8 November 2016, Modi banned the use of high-value notes, sucking 86% of the currency in circulation in one swoop, with the ostensible aim of delivering a body blow to black money hoarders. But the government had perhaps not factored in the fabled Indian ingenuity to subvert the system. So, while the government had hoped that as much as a third of India’s unaccounted wealth would go out of the system, in the end, nearly all the currency found its way back, riding pillion on hundreds of thousands of poor Indians who acted as mules, for a cut, filling up their hereto dormant Jan Dhan accounts, or simply exchanged cash over the counter. The move brought the country’s informal economy to a standstill and dented growth.

Bad loans: This was a problem the Modi government inherited and promised to resolve. Bad debts—now at more than Rs 9 trillion—continue to weigh heavily not just on government-controlled banks but also on its fiscal health. Last year, the government implemented a massive Rs 2.11 trillion recapitalisation plan to keep public-sector banks afloat. But its efficacy is in doubt, especially after Punjab National Bank was hit by a Rs 13,000-crore fraud.

The government also merged the State Bank of India with its subsidiary banks, and could merge several of the remaining 22 state-owned banks among themselves. But it remains to be seen whether these measures will take the massive load of bad debt off their books. It can, however, be safely said that the next regime too will inherit this problem, only at a much bigger scale.

Agriculture: One of Modi’s key poll promises in 2014 was to double farm incomes by 2022. Instead, farm incomes have fallen in real terms, primarily on account of food price deflation and the breakdown in the cash-based rural economy in the wake of the November 2016 demonetisation. In fact, if one compares India’s real GDP growth to expansion of its farm sector, the latter has consistently lagged the former since 2012.

Moreover, the 2018 pre-budget Economic Survey notes that on account of climate change, farm incomes could see a further 25% decline in the long term. Not only has farm distress exacerbated the issue of farmer suicides, it has also brought farmers on to the streets, as happened in Mumbai, when in March this year 20,000 farmers converged upon India’s wealthiest city demanding a complete waiver of loans and power dues. Farmer unrest could cost Modi dearly especially in areas of rural Maharashtra, Karnataka and even Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP’s rival political parties could be quick to cash in on it.

Opportunities

Direct Tax Code: After GST, the Direct Tax Code is the other big tax reform that the Modi government is reportedly looking at implementing. News reports say a draft bill could be introduced in the upcoming monsoon session of parliament. The code could introduce new income tax slabs and cap the corporate tax at 25%.

With these changes, Modi aims to bring some cheer to middle-class Indians by reducing their actual tax outgo and make corporate houses more competitive by reducing their tax liability. If he does manage to pass the direct tax code, the BJP could reap rich dividends in the 2019 elections.

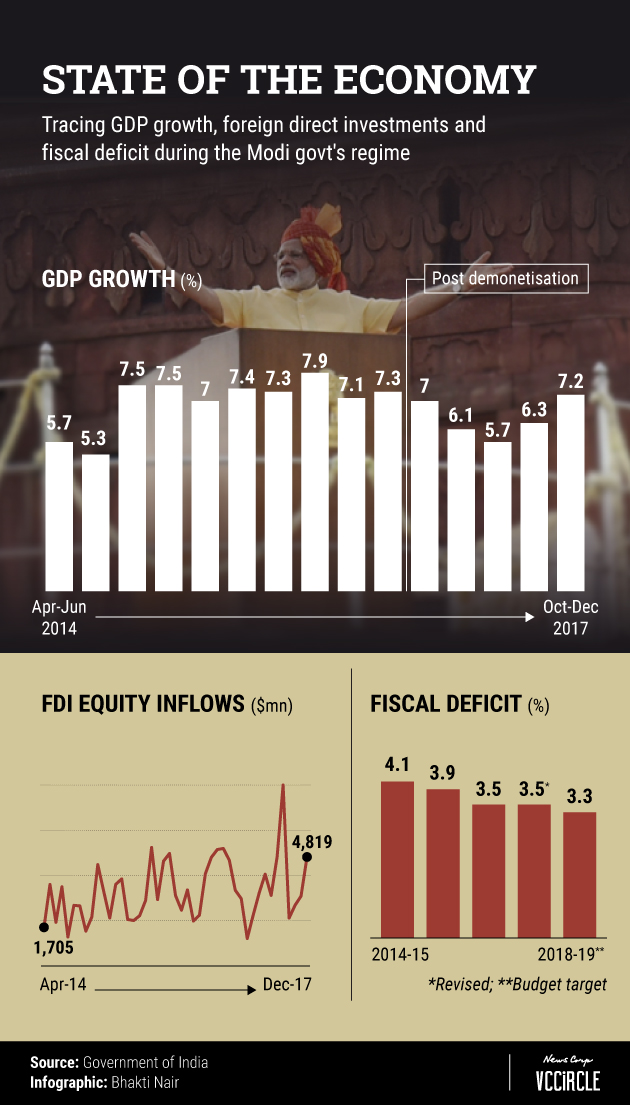

GDP growth: India’s economic growth slumped in the quarters following demonetisation. However, the momentum seems to be back in the recent past, with the December quarter clocking 7.2% growth and India reclaiming the tag of the world’s fastest-growing economy from China. The Modi government would do well to try and keep this momentum going.

But there are some risks ahead. Global crude oil prices have topped $80 a barrel and are unlikely to go down by much in the near term. This could hurt the balance of payments, and lead to a spike in inflation and interest rates. In fact, consumer prices in April rose 4.58% reversing a three-month slide. The Modi government will have to keep its fiscal math in check amid a tough global economic scenario before the next general elections.

Infrastructure (Roads/ Railways// Power): In September 2017, Modi and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe laid the foundation stone for the Ahmedabad-Mumbai bullet train project, which is to be completed by 2022. Although the Modi government has been criticized for prioritising the Rs 1.1 trillion project over other necessary development projects, it does underscore the fact that India’s infrastructure needs an urgent facelift.

In fact, the 2018 Economic Survey says India faces a $526 billion infrastructure investment gap by 2040. In October last year, the government had said it planned to build 83,000 km of roads at a cost of Rs 7 trillion. Railways, power and ports are the other major infrastructure sectors where the government will invest in a bid to kick-start the country’s sputtering economy. Now, if only it could follow through with these lofty promises.

Jobs: If the Modi government plays its cards well, this could well be its biggest trump card yet, even as four-fifths of its time in office is already gone. In 2014, during its election campaign, the government had promised to create 10 million jobs a year. Instead, it ended up creating less than a million in the four years it has been in power.

In the 2018 budget, the government was widely expected to announce a National Employment Policy, which would lay a comprehensive roadmap for job creation, but that did not happen. The government could usher in such a policy now to focus on employment-intensive sectors, especially in the small and medium enterprises space.