The Indian economy had to weather the impact of a double whammy of sorts in 2017. Even as it tried to cope with the demonetisation shocker of November 2016, the government’s decision to roll out the Goods and Services Tax from July crippled it even further, primarily due to faulty implementation of the mammoth step towards overhauling the indirect tax system.

The Indian economy had to weather the impact of a double whammy of sorts in 2017. Even as it tried to cope with the demonetisation shocker of November 2016, the government’s decision to roll out the Goods and Services Tax from July crippled it even further, primarily due to faulty implementation of the mammoth step towards overhauling the indirect tax system.

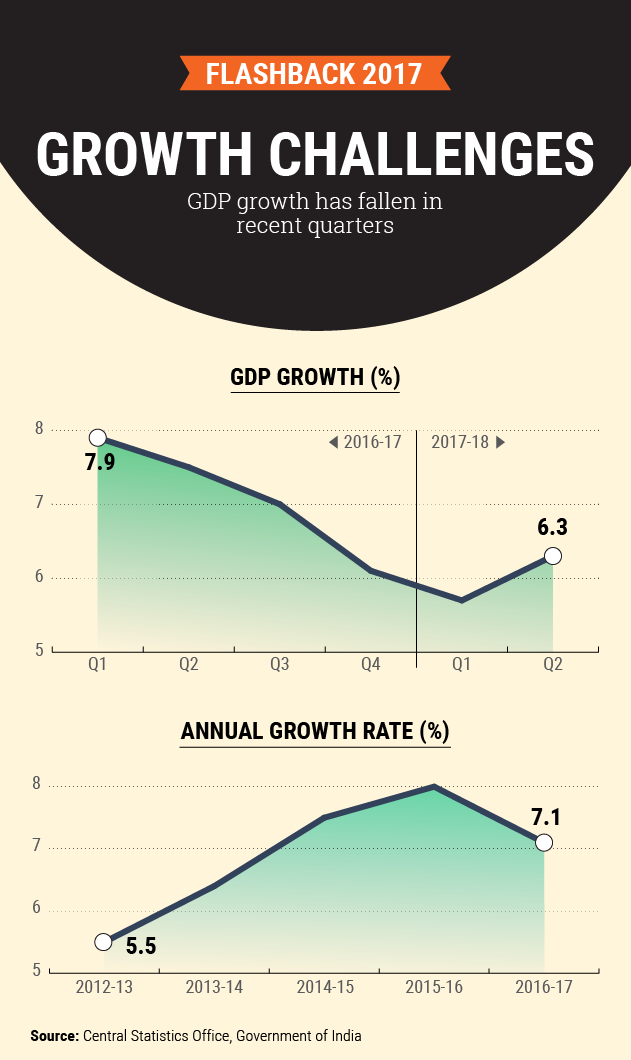

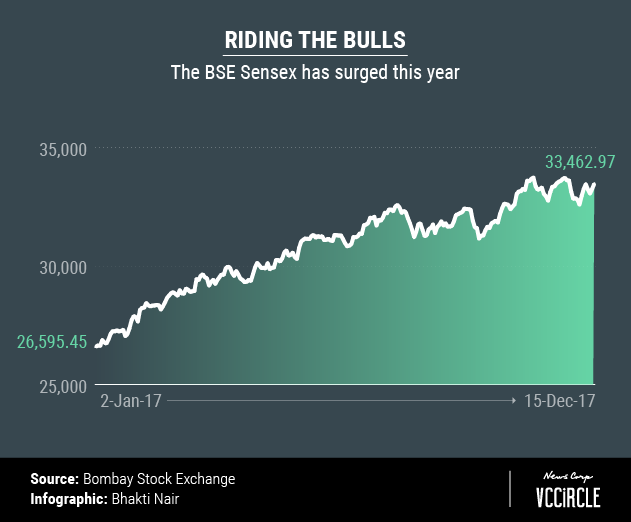

It was, however, also a year of contrasts. On the one hand, economic growth during the first quarter of 2017-18 slumped to a three-year low of 5.7%, before rebounding a tad in the second quarter. But the booming stock market did not seem to either take note of the impact of GST or the note ban move, as benchmark indexes climbed nearly 25% year to date.

Besides, the bad loans problem dragged the banking sector down and crimped lending activity while the agriculture sector’s woes intensified. A rating upgrade, however, by Moody’s and early signs of a recovery in certain sectors were seen as a brief respite. As the year drew to a close, retail inflation raised its ugly head to dampen the mood yet again, with murmurs of an impending rate hike by the Reserve Bank of India looming large.

Overall, India’s economic performance for 2017 was a mixed bag – struggling, but with green shoots of a turnaround visible as the New Year sets in.

The bad

The year started with the economy reeling under the note ban move, leading to the near-demise of small businesses, especially in the cash-dependent informal sector, besides bringing down infrastructure, including real estate, to its knees and crushing consumer demand.

While the construction sector remained sluggish, especially due to slowing demand of finished steel and cement, the biggest concern was agriculture, which continued to be under stress with growth slowing in the second quarter to 1.7%, compared with the 4.1% clocked in the year-ago period.

Despite the Narendra Modi government’s efforts to tackle bad loans that plague a significant chunk of the country’s state-owned banks, the problem remained the elephant in the room during the year without significant progress and seeking urgent attention. In October, the government announced a mammoth recapitalisation plan of Rs 2.11 lakh crore for public-sector banks.

The corporate debt overhang and the banking sector’s soured loans kept private investments under pressure. Government data show that gross fixed capital formation, a proxy for gauging investments, slumped to 1.6% growth in the April-June quarter. The situation, however, improved in the second quarter with growth coming in at 4.7%. Still, that’s not enough.

Ratings firm India Ratings said in a recent report that a recovery in the investment cycle is unlikely before 2019-20 due to muted demand and high debt levels and that government efforts will also be ineffective. The unit of global ratings firm Fitch also said that companies will shy away from investments despite the prevailing low interest rates.

To compound the problem, interest rates may start picking up next year as news of retail inflation zooming to a 15-month high of 4.88%, breaching the central bank’s 4.2-4.6% target range, fanned speculation monetary tightening.

The good

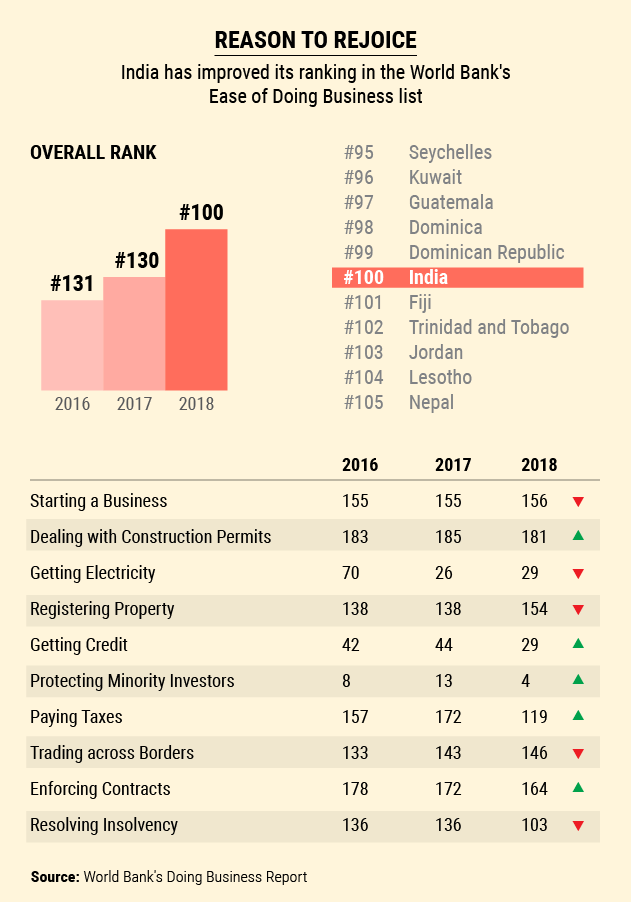

However, it was not all doom, gloom, confusion and heartburn for the Indian economy. This was highlighted by the Indian stock market scaling new highs, and India rising 30 places in the World Bank’s doing business report, reaching the top 100 in the world for the first time.

The concerns over the GST and demonetisation did little to affect the equity markets, with the Sensex hitting record highs to breach the 33,000 mark thanks to ample global liquidity and rising inflows into mutual funds as the cash economy moved to organised channels after demonetisation.

It was also a bumper year for stock market debuts, with as many as 37 initial public offerings raising more than Rs 71,300 crore.

In fact, as a VCCircle analysis showed, the IPO boom helped equity capital market transactions overtake private equity deals by value after almost a decade. Part of the reason was, however, the sluggish PE dealmaking scenario.

One of the most successful IPOs was that of retail chain D-Mart (Avenue Supermart), which listed at a premium of over 100%, propelling its promoters, the Damani family, to India’s elite billionaires club.

The central government was the biggest beneficiary of the IPO boom, given that several state-owned companies, including General Insurance Corp of India, New India Assurance, Cochin Shipyard, Housing and Urban Development Corp, went public this year. This may help the government meet its disinvestment target and keep the fiscal deficit under control.

The good news for the government, at least, as far as optics go, did not just end there. In November, credit rating agency Moody’s gave the Indian economy a ratings upgrade to Baa2, from Baa3, something the government went to town with.

Moody’s, in fact, said that the blip in India’s growth momentum was a “temporary impact of demonetisation†and that it expected India’s GDP growth to bounce back to 7.5% in 2018-19.

A sector-wise analysis also showed that India’s gross domestic product (GDP) may witness a phase of growth with the manufacturing sector in the second quarter of 2017-18 growing at 7%, compared with 1.2% in the previous quarter. The trend indicates a revival in jobs growth and, consequently, in demand.

The year was also notable for the merger of State Bank of India (SBI) with its five associates, besides the Bharatiya Mahila Bank. The merger could be a precursor to a trend that might see more consolidation in the sector.

Where we stand

The economy seems to have finally moved over the immediate impact of demonetisation, but GST may remain a thorn in the flesh for a couple of quarters more. It was evident that the government was in a hurry and not particularly well prepared before the 1 July rollout. The GST Network, the tax system’s technology backbone, struggled to cope with several issues, leaving traders perplexed.

In fact, the overall state of confusion and partial disarray that ensued was, at least, partly responsible for indirect tax collections taking a hit. October GST collections were down by nearly 10% to just over Rs 83,300 crore, the lowest since the new tax system was implemented, down from Rs 92,150 crore in September, Rs 90,669 crore in August and Rs 94,063 crore in July.

The tax system was overhauled in November when as many as 178 items were moved from the 28% tax bracket to 18%. Subsequently, India’s chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian said that the government could further simplify the tax regime.

But there is still plenty of work to be done to make it a fool-proof system. For one, say analysts and traders, the paperwork around GST is tedious, and slow internet speeds, especially in India’s hinterlands, make GST compliance an arduous task.

“Not only are traders facing issues with the system, a good number of them are managing to bypass the system, and managing to avoid paying GST. And so far, the government has taken no punitive action against them,†says Sudhir Panwar, a farmer leader and former member of Uttar Pradesh State Planning Commission.

The Modi government also tried to sort out the bad loans problem. It gave more teeth to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code that was enforced last year. In November, it promulgated an ordinance that debars defaulting promoters from bidding for their own companies when they were being auctioned by the bankruptcy courts. Yet, as a VCCircle analysis noted last month, several key aspects, including compliance issues may have been completely overlooked.

RBI stands guard

Throughout 2017, the RBI kept interest rates steady, but the rise in retail inflation beyond its comfort zone could prompt it to go for a rate hike early next year.

Although brokerages were divided on whether the latest inflation numbers will force the RBI’s hand in raising interest rates, they contended that it is a red herring, nonetheless. While analysts at IDFC and Motilal Oswal do not expect the central bank to hike key policy rates, those at Nomura believe that rising core inflation risks a status quo on policy.

DK Srivastava, chief policy adviser at EY India, however, does not see interest rates going up in February, when the RBI meets for its next policy review. “Status quo is likely to continue, because the higher inflation numbers are given largely by vegetable prices or other influences. This should not really effect the core considerations for making the interest rate policy.â€

As 2017 comes to an end, the Indian economy and stock markets seem to be on the tenterhooks – more so, as the country enters a pre-election year, the central government may be forced to tread a cautious line between pragmatism and populism.

This, at a time when the after-shocks of the November 2016 demonetisation move, could linger on this New Year. “I think some businesses in the informal sector, which closed down, may never come back into their original form, so that impact will remain,†says Srivastava.