The political risks were enormous and the economic gamble was even more pronounced, but that did not deter Prime Minister Narendra Modi from announcing the withdrawal of high-value currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 as legal tenders on 8 November 2016.

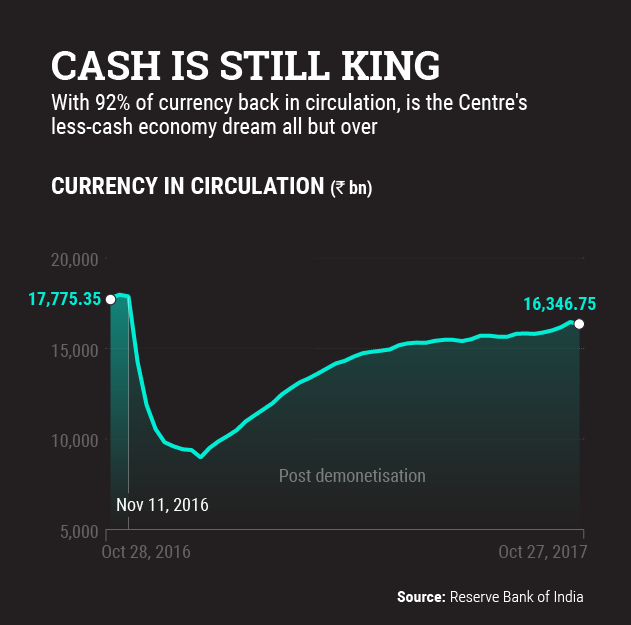

Sure, the decision to suck out Rs 15.4 trillion of the nearly Rs 18 trillion, or 86%, of the currency in circulation was a bold move, and maybe well-intentioned, but before all of India could realise what had hit them, the tsunami of a reforms move had dashed the hopes of many – the daily-wager, the small merchant and a huge section of the unorganised sector, which is a vast and significant segment of the Indian economy.

The long serpentine queues outside ATMs and banks over the next few days, weeks and months, were only a side kick to the story that unravelled in the rural economy, where people lost their livelihoods and small businesses had to shut shop.

One year on, the jury maybe still out on the economic reasoning behind demonetisation, but most people, whether in public view, or within closed doors, have either questioned the central government’s preparedness to implement such a move, or have called it “organised loot and plunder”.

In the short-term, however, the political gamble by Modi surely paid rich dividends with the BJP coming to power in several states during the year. The absolute majority in the Uttar Pradesh assembly was the cherry on the cake.

But, even after 12 months, the economy is yet to revive from the impact of demonetisation.

While Modi, his colleagues in the government and the economists at the Reserve Bank of India believed that the sudden shocker would be a smart move to shoot several birds down with a single shot, it was a misadventure that should have best been avoided.

In fact, the tall claims by the Prime Minister on how demonetisation would help curb the menace of black money, weed counterfeit currency out of the system and strike a body blow to terror financing, besides formalising a significant portion of the country’s informal economy, have mostly fallen flat.

And, with 92% of the currency back into the system, the initiative to make India a less-cash, digital economy seems to have also taken a hit with the share of value transacted through mobile wallets touching pre-demonetisation levels, despite an increase in transactions as well as the user base.

However, overall, digital payments have seen an increase in usage and transaction value across instruments, including debit and credit cards, net baking and prepaid payment instruments.

Modi and his government had, in fact, undermined the ingenuity of the Indian mind in turning black into white – the wealthy not only used the less fortunate as ‘mules’, but also used shell companies to convert the banned notes into legal tender.

While the central bank did eventually freeze the zero-balance Jan Dhan accounts, which had suddenly sprung to life from their dormant slumber, besides imposing withdrawal limits on the other accounts, it was a case of too little too late.

The admission by the RBI that Rs 15.28 trillion, or 99% of the demonetised currency, had made its way back in the banking system, was in itself a lost cause. This, when the central bank had initially hoped that at least Rs 3 trillion in untaxed wealth will not return.

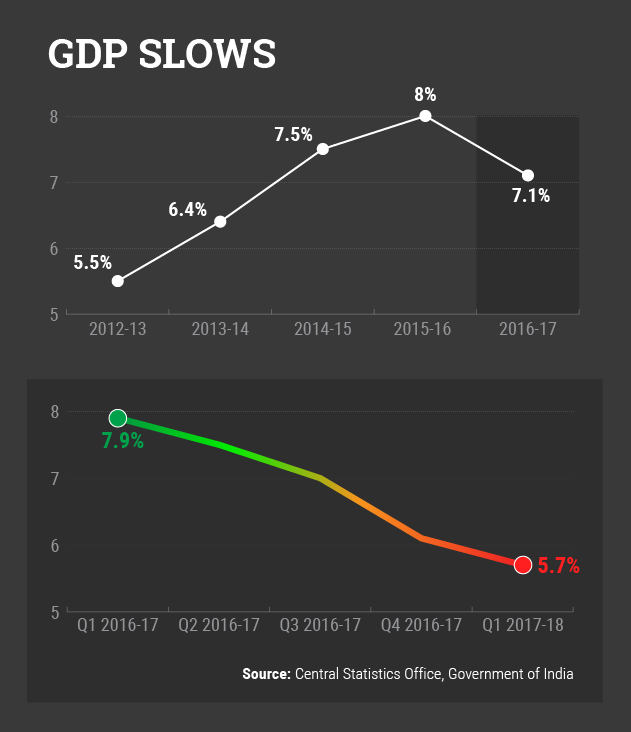

The move also virtually paralysed large swathes of India’s cash-dependent economy, singeing growth.

While the quarterly growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) came crashing down from 7.9% in the first quarter of 2016-17 to 5.9% in the corresponding quarter of the current financial year, India, which was one of the fastest growing big economies, also saw its pace of growth grind down to 7.1% in 2016-17 from the highs of 8% during the previous financial year.

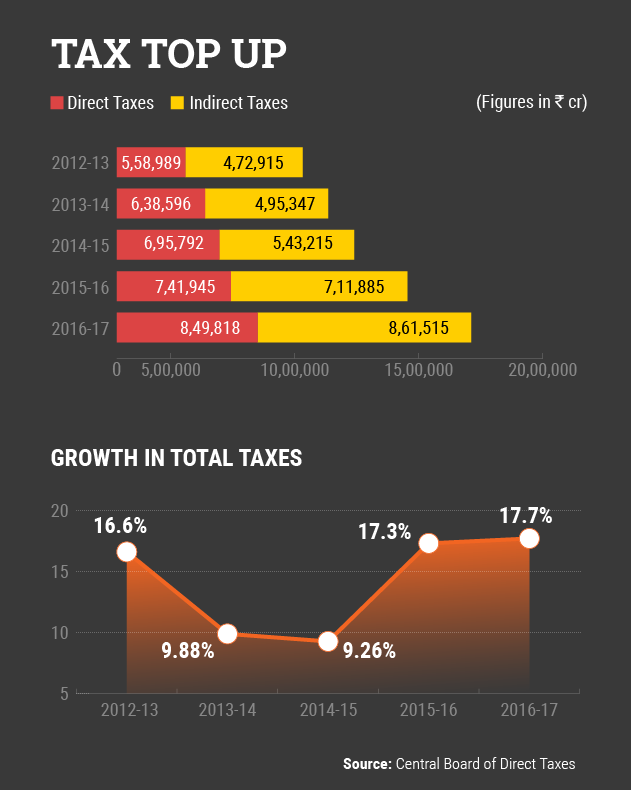

Yet there was a silver lining, as India’s tax collections saw a healthy 17.7% increase with both direct and the indirect tax collections growing handsomely by Rs 1.08 trillion and Rs 1.5 trillion, respectively. This, evidently, was because of higher tax compliance.

Having said that, real estate and gold, the two principal havens for unaccounted and untaxed income, however, proved to be resilient to the shock of the note ban.

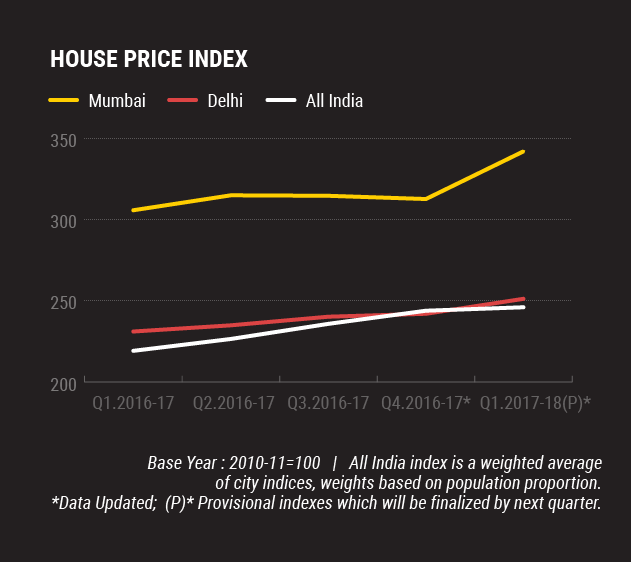

Anecdotal evidence suggests that in the immediate aftermath of the move, cash deals in real estate came to a virtual standstill, and prices corrected, at least for the short-term. However, the central bank’s data show that the country’s house price index actually went up in the two quarters post demonetisation. In fact, registered sales, at least across 10 major cities in India, had not been impacted.

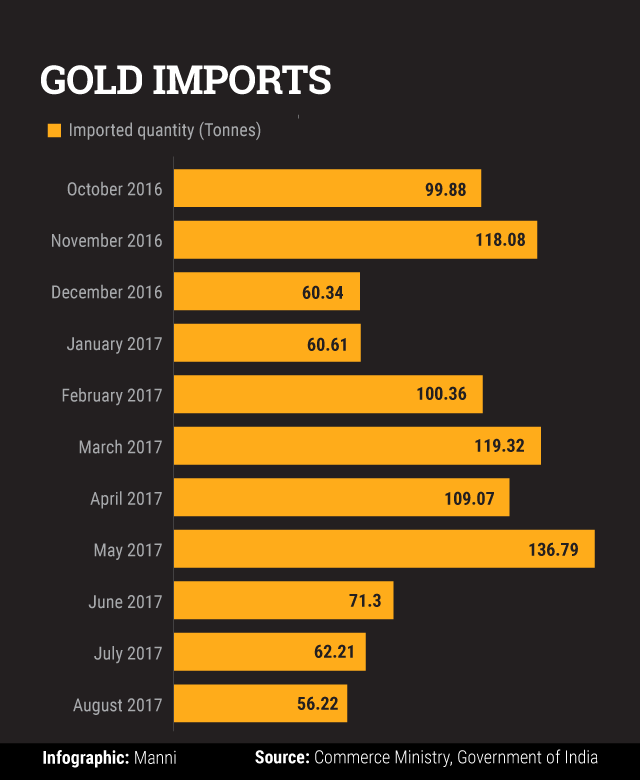

Similarly, the move had only a transient impact on gold imports, which also account for a lion’s share of India’s forex outgo. While import of gold nearly halved in the two months following demonetisation, in February it perked up to cross the 100-tonne mark. In March 2017, Indians imported more gold than they had done in November 2016.

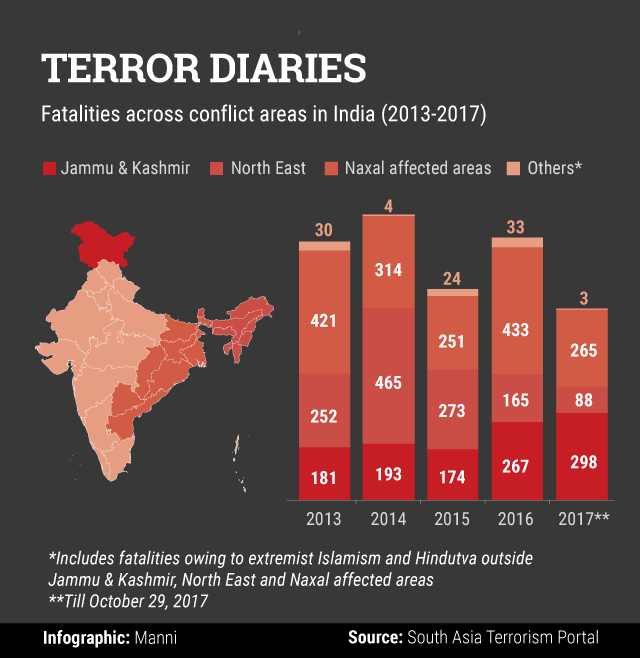

Modi can, however, take heart from the fact that it perhaps did have some positive impact on terrorist activity in India. While there is little official data, figures put out by the South Asia Terrorism Portal, a repository of information on homeland security in the region, indicate that fatalities due to violence across naxal-affected areas show a marked decrease over the past year. By October-end, it recorded 265 deaths due to naxal violence, against 433 during 2016. The North East, too, saw violent clashes taking 88 lives, compared to 165 in 2016. However, the Kashmir Valley has already seen more people die in the first 10 months of the current year than last year.