Real estate is a critical sector, both from an economic and social point of view. It contributes about 10% to India’s gross domestic product and is a significant source of mass employment, directly and indirectly. From a social point of view, various estimates peg the annual housing demand (rural and urban) at 10 million homes a year, driven by long-term demographics trends, urbanization and nuclear families.

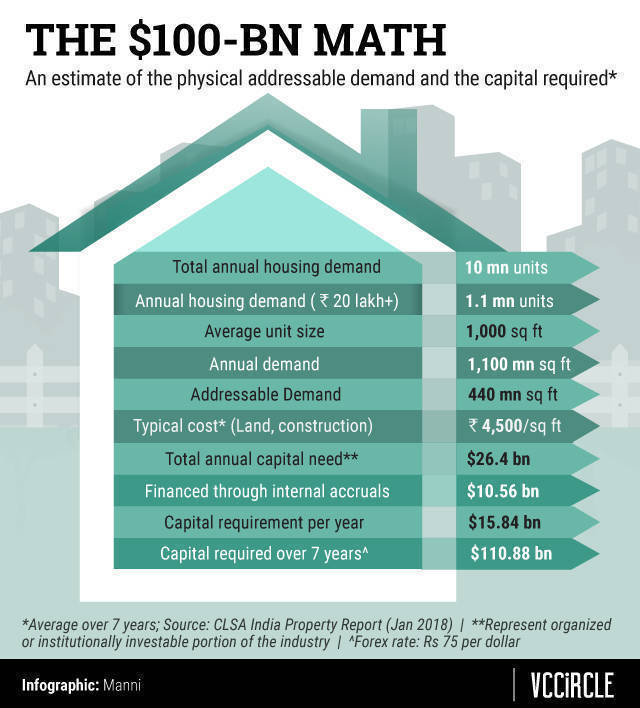

But the sector is a capital guzzler, often with wild swings in availability of the same. In our estimate, the housing sector alone needs more than $100 billion over the next seven to 10 years. Coupled with demand from other asset classes (office, warehousing, retail and hospitality), the total need is almost $130 billion.

The math is simple and derived only from institutionally focused or addressable segments of the total demand. A significant portion of this demand is in the low-income category (Rs 20 lakh or lower) with limited institutional focus. But even the more focused segments (mid-income and higher) have an annual requirement of about one million housing units.

The estimate is based on the future need and does not provide for the solutions required on existing wholesale real estate exposures held by non-banking finance companies or housing finance companies.

The last decade

The sector opened for foreign investment in 2005 and was soon flushed with capital, given the exuberant environment before the global financial crisis. After the crisis in late 2008, the physical markets took a hit but the drop was short-lived. Residential markets rebounded handsomely, clocking an annualised price growth of about 15% for close to five years before starting to cool off in 2014.

During this period, capital availability was severely restricted, pushing returns to over 20% for debt-like investments. This attracted new players, initially those with real-estate investing or lending expertise. By 2013-2014, high-yields lured non-focused or retail lenders into wholesale real estate lending business.

Between 2013 and 2018, NBFCs and HFCs accounted for 75% of the asset growth in wholesale real estate debt thanks to cheap and easy liquidity. During this period, debt mutual funds grew their assets under management by $100 billion and accounted for 80% of subscription to NBFCs’ commercial paper.

All of this came to a grinding halt when IL&FS defaulted in September 2018. Credit access to several NBFCs and HFCs froze. Since then, several other institutions have defaulted, highlighting asset-quality and asset-liability issues.

Current situation

For a large part of the real estate sector, the pendulum has swung from one extreme to the other – from easy and abundant liquidity to practically no capital.

Non-specialized players are exiting this space or scaling back. Focused incumbents are also on the back foot due to non-availability of growth debt capital. Banks are unlikely to fill the gap due to limited underwriting focus on wholesale real estate, regulatory restrictions and higher capital allocation requirements due to higher-risk weightage mandated by the RBI.

As several of these incumbents change their business models or downsize due to asset-liability side issues, part of the $50 billion in existing exposure sitting with NBFCs and HFCs needs to find a new home.

Since the onset of credit crises with the IL&FS default, foreign investors have invested or are in discussions to invest about $2 billion towards such exposure. But there is still a long way to go.

This capital vacuum is intensifying consolidation in the sector, which was already underway after the implementation of the real estate regulatory law RERA, the Goods and Services Tax and demonetisation.

About 263,000 units, totalling 250 million square feet, across projects are either on hold or delayed due to financing and liquidity challenges. Even fundamentally strong projects are finding it difficult to access capital. For many, yields have spiked to 20% for senior debt-type capital.

View on the future

Demand for housing in India is structural, driven by demographic and social trends. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic-induced disruption has put a premium on home ownership. Cyclically, the last seven years were characterized by several disruptive events. We believe this down cycle is bottoming.

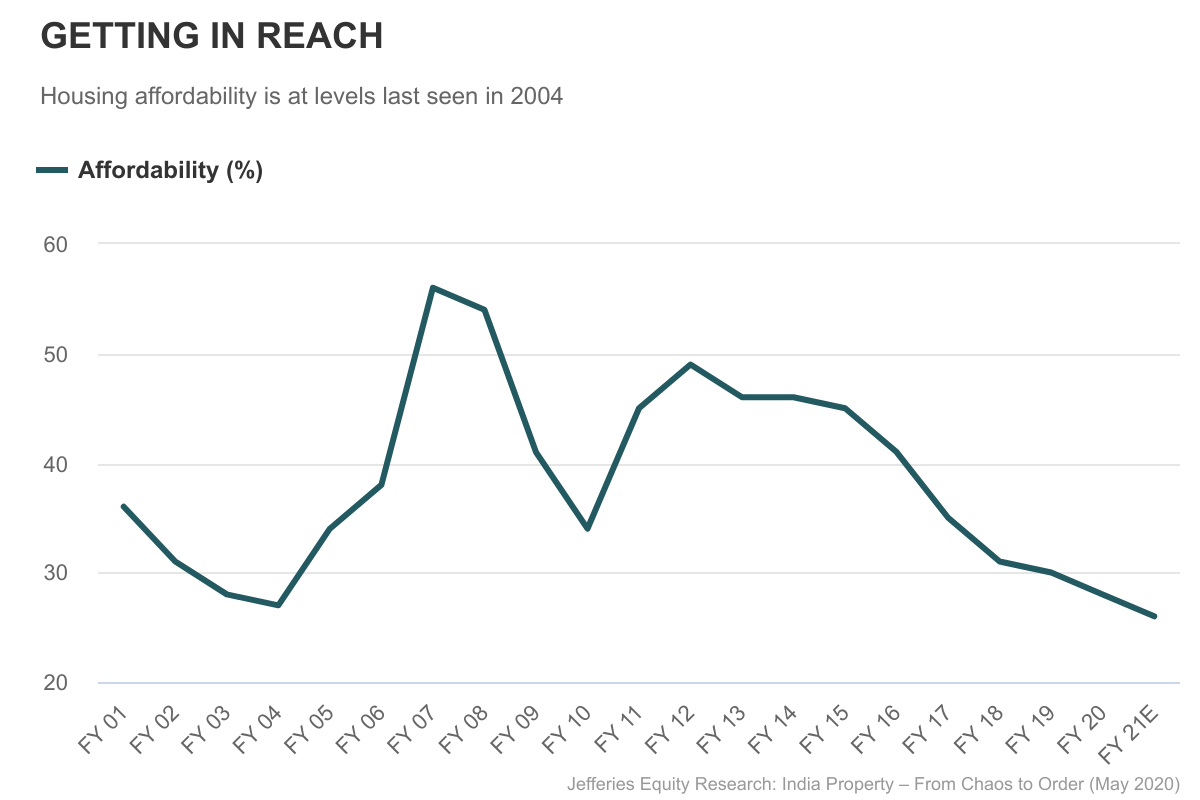

Affordability is at levels last seen in 2004, driven by 15-year low mortgage rates and benign property prices where growth has trailed inflation for the last seven years. Add to that discounts being offered by developers, stamp duty reduction in certain markets and other recent reforms, the overall package has become compelling for the buyer. Recent sales performance (significantly up from year-earlier levels) and near-term expert projections provide early evidence of this view.

On the one hand, where we expect the start of a new demand cycle, supply is likely to moderate. To begin with, tight liquidity conditions constrain capital required for new starts.

This is further exacerbated by increased working capital requirement due to RERA-imposed discipline and a shift in consumer buying preference to late-stage projects.

Overall, we expect these trends and accelerating sector consolidation to lead to significant supply discipline, both in terms of quality and quantity.

Conclusion

The solution to current capital woes ultimately lies in continuous sectoral reforms (state-level regulatory and procedural reforms rather than fiscal incentives) and restart of domestic credit flows to the sector.

No other source of capital can plug the massive needs of the sector. Domestic institutions, however, remain fearful and are unlikely to come back in a hurry.

In the meanwhile, it is yet not clear who will step in to fill the massive gap left by these retreating incumbents. In this, we see an urgent need and an opportunity. The current vintage feels unique and rare.

Ashish Khandelia is the founder of Certus Capital.