Last week, California-based Virgin Hyperloop One inked memoranda of understanding with the governments of Karnataka and Maharashtra to examine the feasibility of building Hyperloop routes. The development came just two months after its competitor Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, also known as HTT, signed a similar pact with the state of Andhra Pradesh.

While the benefits of a fast and efficient mass transport system for developing and populous countries cannot be stressed enough, India presents a unique set of challenges. The extreme capital-intensive nature of projects involving emerging technologies, the accompanying cost overruns, and yet-to-be-ascertained operational costs could well put the tickets beyond the reach of the common man—the raison d'être of the initiative. Besides, tricky issues like land acquisition, among others, have thrown a spanner in the works of many an infrastructure project in India. But more on that later.

First, let us understand how Hyperloop aims to revolutionise mass transport.

Drawn up as a concept by Tesla founder Elon Musk in 2013, Hyperloop comprises a system of tubes through which a pod may travel free of air resistance or friction at high speeds. Put simply, it is a transport system where a hybrid, train-like object can travel at speeds over 1,000 kmph in a near-vacuum tunnel.

The first project, Alpha, proposed examining a route from the Los Angeles region to the San Francisco Bay Area. A paper claimed that the transport system could carry passengers along the 560-km route at an average speed of around 970 kmph, and a top speed of 1,200 kmph. That meant it could complete the journey in just 35 minutes, way faster than rail or air travel. However, the paper also pegged initial cost for the route at $6 billion for a passenger-only version, and $7.5 billion for a somewhat larger-diameter passenger-cum-vehicle version.

Relevance for India

At about 150 km, the cities of Mumbai and Pune are about three hours apart. Deploying Hyperloop on this route can bring down travel time to a mere 14 minutes, resulting in India’s "first and largest megapolis", Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis said last week.

Similarly, it will allow people to travel from Delhi to Mumbai, India's busiest route, in just 70 minutes, almost half the time taken by a flight.

Analysts believe a national Hyperloop system will bring a lot of positives for the economy, notwithstanding the huge costs of setting it up.

“India is home to one of every six humans on the planet. The average Indian commuter spends 91 minutes idling in crowded streets. Traffic delays cost the economy Rs 43,000 crore ($6.6 billion) per year, and a staggering Rs 96,000 crore ($14.7 billion) including fuel costs. Overcrowding is also a big issue for India’s giant rail network, which moves more than 23 million passengers daily—nearly the entire population of Australia,” a senior business analyst working for Hyperloop One explained.

Jostling for a pie

With the central government making its intent clear as far as infrastructure development is concerned, and state governments following its lead, Virgin Hyperloop One and HTT have stepped up efforts to grab a piece of the pie. Though the projects are still at the feasibility study stage, earning the confidence of state governments and proving technological and operational competence will lay the ground for these players.

Los Angeles-based Hyperloop One, founded by Shervin Pishevar and Brogan BamBroganin, and led by CEO Rob Lloyd, entered the country in January. Its executives met government officials to work out ways to implement Hyperloop projects between major cities. In late February, it held a summit in the presence of the then railway minister Suresh Prabhu and NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant to discuss how Hyperloop can augment India’s vast transport network.

“A transportation system like the Hyperloop will undoubtedly ease the pressure on existing infrastructure while enhancing the quality of life of the people. We are already working with the governments around the world on passenger and freight projects, and we look forward to partnering India,” Lloyd had said.

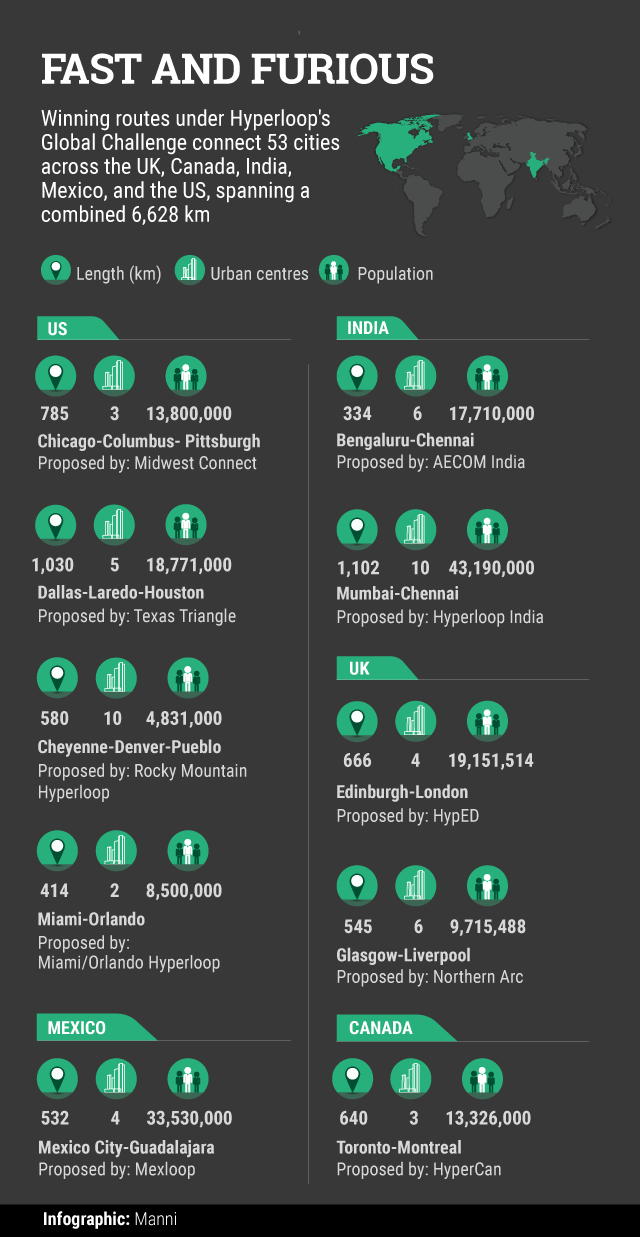

Earlier, Hyperloop One kicked off its Global Challenge in May 2016, calling for comprehensive proposals to build networks connecting cities around the world. More than 2,600 teams registered globally, and the company narrowed it down to 35 semi-finalists with a potential pipeline worth $26 billion. India, Hyperloop One said, led the way with the highest number of registrants.

Notable participants from India were AECOM, which proposed a 334-km Bengaluru-to-Chennai corridor to be covered in 20 minutes; LUX Hyperloop Network, which proposed a 736-km Bengaluru-to-Thiruvananthapuram corridor to be covered in 41 minutes; Dinclix GroundWorks, which proposed a 1,317-km corridor connecting Delhi and Mumbai via Jaipur and Indore in 55 minutes; Hyperloop India, an 1,102-km route between Mumbai and Chennai via Bengaluru to be covered in 50 minutes; and Infi-Alpha, which proposed a 334-km route between Bengaluru and Chennai to be covered in 20 minutes.

In September this year, the company selected 10 routes and teams as winners of the Global Challenge (see graphic). AECOM's Bengaluru-Chennai route and Hyperloop India's Mumbai-Chennai route made the cut.

“This network could create the largest connected urban area in the world by linking nearly 75 million people across the three metropolitan areas of the states of Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh to improve global competitiveness, reduce congestion and emissions, and provide citizens with better social and economic mobility,” Hyperloop One had said in a statement.

Plans are afoot to connect spots within and around the city, too. The company has said it was looking to link Bengaluru’s city centre, IT hubs and industrial parks, as also improve connections between industrial hubs in the state such as Tumakuru, Hubli-Dharwad and Hosur.

The company says it has secured $160 million in funding, and is on its way to raise more capital.

However, it also expects the Indian government to source funds for the two projects.

Hyperloop One's rival HTT has not been sitting quiet either. In February, the company said it had offers from five Indian states to start feasibility studies and initial work on building Hyperloop projects. Apart from Andhra Pradesh, it is in talks with Tamil Nadu, Odisha and Jharkhand.

Reports suggest that the company has roped in at least two Indian companies to build Hyperloop projects, including vacuum tube maker Leybold and engineering company AECOM.

Founded in November 2013, HTT uses a crowd-collaboration approach. It claims that it can finish a Hyperloop network in 38 months once all the approvals are in place.

HTT's co-founder Bibop Gresta says his company uses a technology different than One's, and its approach is greener—it uses passive levitation against One’s active levitation. He also said that HTT used an aluminium track, and its capsule was combined with electromagnets in a way so as to work on low volumes of electricity. A ticket for a 500-km distance on HTT's Hyperloop may cost under $30 (about Rs 2,000), Gresta explained.

Gresta, however, seems wary of the costs involved in setting up the infrastructure. He said that laying a kilometre of Hyperloop track would cost between $20 and $40 million.

HTT claims to have invested $32 million so far across projects in the UAE, Slovakia and the US. It has raised $100 million so far—$30 million in cash and an additional $70 million in land rights and services.

Hyperloop vs bullet trains

HTT's Gresta has been very vocal in criticising India’s efforts on the bullet train front. In several media interviews, he has suggested that a $1 billion investment in Hyperloop is way better than a similar investment in bullet trains, which use dated technology. Besides, the bullet train will also take a long time to be set up, he says.

However, transportation analysts VCCircle spoke to felt that Hyperloop projects could run into huge cost overruns taking into account construction, development and operational costs.

At the same time, some experts don’t agree with Gresta on Hyperloop’s superiority over bullet trains.

“We can’t compare Hyperloop with bullet trains as the former is a very new and unproven technology.

Bullet trains have been in existence for the last 35 years,” said Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman of Feedback Infra, a company that provides technology services in the energy, transportation and realty space.

“India is much better off right now with bullet trains... What the two companies are doing in India is a PR exercise for raising more money from investors,” Chatterjee said, adding that the two foreign players needed to lay a sizeable test track of at least 20 kilometres to prove the project's effectiveness.

“A successful test in Nevada is not enough to cut it,” he remarked.