India on Friday outlined steps to attract greater foreign capital, ease stress on lenders struggling with bad loans and give up control of state-run companies, as it sought to boost investment and accelerate economic growth.

India on Friday outlined steps to attract greater foreign capital, ease stress on lenders struggling with bad loans and give up control of state-run companies, as it sought to boost investment and accelerate economic growth.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, presenting the budget for 2019-20 in parliament, also proposed to give greater powers to the central bank, deepen the bond market and expressed an intent to reform India’s complex labour laws.

The budget, the first since Prime Minister Narendra Modi stormed back to power in May, comes in the backdrop of slowing growth, tepid corporate investments, high unemployment and global headwinds such as a trade war.

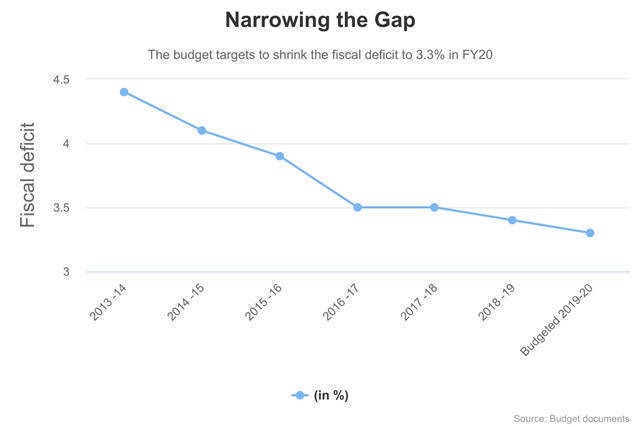

Sitharaman narrowed the fiscal deficit target for the current fiscal year to 3.3% from 3.4% last year—a surprise move—as she budgeted an increase of just 13.4% in government expenditure.

To keep the fiscal deficit in check, she estimated gross tax revenue to rise 9.5% and jacked up the disinvestment target by nearly a third to Rs 1.05 trillion ($15.3 billion). The fact that the tax revenue growth target is so low raises doubts about the government’s ability to accelerate economic growth and revive consumption that could prompt companies to increase investments.

Overall, the budget’s main theme appears to be unleashing reform in areas as diverse as foreign investments and labour laws. But it also unveiled a range of smaller measures for everyone—except the middle-class taxpayer—so much so that ratings firm Moody’s said the budget was chasing a whole host of “competing goals”.

Moody's preliminary comments on India's #Budget2019 (1/4) pic.twitter.com/sU3RYaVErT

The finance minister did not specify any significant changes to the labour laws, but she did say that the government will streamline multiple laws into a set of four labour codes. “This will ensure the process of registration and filing of returns gets standardised and streamlined. With labour definitions getting standardised, it is expected that there will be less disputes,” she said.

While one of the four proposed labour codes—on wages—is awaiting parliamentary approval, the new industrial policy, which was finalised by the commerce ministry last year, is awaiting cabinet approval.

Disinvestment

For one, the finance minister signalled in no uncertain terms, her government’s intent to get out of the business of doing business. To be sure, past governments, too, have shed stakes in government-owned companies. But it is perhaps for the first time since the Atal Behari Vajpayee regime, which was voted out of power in 2004, that the government is again talking about offloading majority stakes in companies it owns to private players.

Sitharaman said that the government has been diluting its stake in non-financial companies but keeping its holding above 51%. That could now change.

“The government is considering, in case where the undertaking is still to be retained in government control, to go below 51% to an appropriate level on a case-to-case basis,” Sitharaman said. “The government has also decided to modify the present policy of retaining 51% government stake to retaining 51% stake inclusive of the stake of government-controlled institutions.”

In fact, just last year, the government had done something similar when it had offloaded a majority stake in oil refining and marketing company Hindustan Petroleum Corp (HPCL) to explorer ONGC Ltd for a little under Rs 37,000 crore. Sitharaman’s comment indicates more of the same could happen if the government does not find private-sector suitors for state-run companies.

“In view of the current macro-economic parameters, the government would not only reinitiate the process of strategic disinvestment of Air India, but would offer more CPSEs for strategic participation by the private sector,” the finance minister said, as she raised the disinvestment target this year from Rs 80,000 crore last year to Rs 1.05 trillion.

Apart from a higher disinvestment target, the government plans to balance its books by accounting for a significant increase in dividend incomes from the Reserve Bank of India and public-sector banks. This year’s budget has accounted for Rs 1.06 trillion as dividend income from the RBI and other banks, as against Rs 72,100 crore last year.

In a media interaction following the budget speech, finance secretary Subhash Chandra Garg said the RBI’s share of the dividend could be around Rs 90,000 crore. To be sure, the final number will be approved by a panel headed by a panel headed by former RBI governor Bimal Jalan later this month.

Bank recapitalisation, sorting out the NBFC mess

Besides disinvestment, the other significant focus of the budget was the banking and the shadow banking sector, which has been reeling under the aftermath of a burgeoning crisis of toxic assets.

On the one hand, the finance minister announced an additional Rs 70,000 crore infusion into public-sector banks. On the other, she said these banks will get a partial government guarantee to buy NBFC assets to the tune of Rs 1 trillion in the coming six months.

Sudhir Kapadia, national tax leader at EY India, said that these two measures are attempted to address some of the financial stress in the economy, which has arguably led to lesser private sector investment.

But he added that India Inc. “may be disappointed at (the) relative lack of specific measures” to stimulate demand in the economy.

Tax proposals

The finance minister raised the threshold for the lower corporate tax rate of 25% to companies with a turnover of Rs 400 crore from the earlier Rs 250 crore. This, analysts like Kapadia said, did not go far enough.

“The reality is that it is the large companies which have a great contribution to the overall economy and they are still taxed at the higher rate of 30%,” Kapadia said.

The budget didn’t tinker with the personal income tax rates or slabs, and in fact, increased the surcharge on people earning more than Rs 2 crore. It also increased customs and excise duties on several products such as petrol, diesel and gold. This effectively means the taxpaying individuals aren’t getting any extra money in hand and will have to pay more for some goods.

Kapadia said there has been an increase in the maximum marginal rates of taxation at higher-income levels and there is no meaningful reduction in indirect tax rates. “It seems that the desired push for consumption may not be seen,” he added.

In yet another reform-oriented move, the finance minister announced an amnesty scheme for disputes from the time the central excise and services taxes were in vogue, before they were subsumed under the GST. She said that more than Rs 3.75 trillion was locked in such litigation and that there was a “need to unload the baggage and allow the business to move on”.

Easing FDI norms

In a bid to bring in more foreign investment, Sitharaman proposed easing of norms for foreign direct investment across several sectors including media, animation, aviation and insurance. While 49% FDI is already permitted in the aviation sector, newspapers and periodicals are allowed to have up to 26% foreign ownership.

The finance minister said that the government was considering permitting 100% FDI for insurance intermediaries while it will also look at easing local sourcing norms for single brand retail.

Further, the minister said that in order to invite greater participation from foreign investors, the government will relax KYC norms for foreign portfolio investors, and merge non-resident Indian (NRI) portfolio investment scheme route with the FPI route to encourage more NRIs to invest in the country’s capital markets.

All in all, said EY’s Kapadia, some of the policy measures announced would go a long way in removing the challenges on financing faced by businesses and increasing economic activity.

“However, in the short term till such policies get fully implemented, there is relative lack of demand stimulus which India Inc was hoping for to accelerate economic growth.”