On 23 January, the International Labor Organisation (ILO) said that more than three-fourths of India’s workforce will be vulnerable by 2019.

On 23 January, the International Labor Organisation (ILO) said that more than three-fourths of India’s workforce will be vulnerable by 2019.

According to ILO’s World Economic and Social outlook Report, while 77% jobs in India will be vulnerable, unemployment would increase in 2018 to 3.5% from 3.4%, affecting 18.6 million people from 18.3 million last year. By next year, the situation would be worse with 18.9 million people without jobs.

The statistics will certainly be on finance minister Arun Jaitley’s mind as he gets ready to deliver the last full budget of the Narendra Modi-led government’s first term in office on 1 February. More so, as Modi had come to power four years ago on the promise of creating jobs.

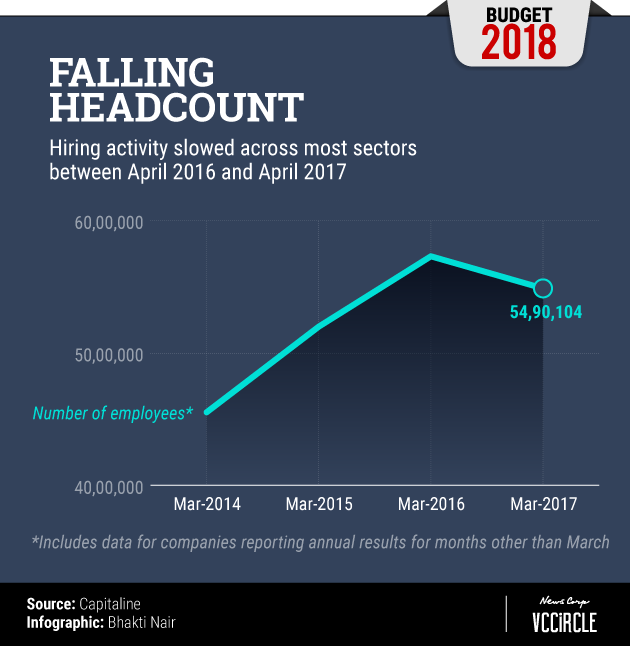

However, Jaitley’s woes do not end here. A VCCircle analysis of listed companies shows that the employee count had come down by a little over 4.2% in 2016-17, year-on-year, to 242,000. In contrast, the first two years of the Modi government had seen the employment numbers increasing by a fair bit.

However, the data sourced by VCCircle is not exhaustive, given that the number of employees is not reported by all companies, and the fact that many local firms and Indian subsidiaries of global majors are not listed on the exchanges.

Yet, the trend for corporate India is clear. In the one year to March 2015, the employee count by listed companies rose from 4.5 million to 5.2 million and, in the following year, it went up to 5.7 million. But 2016-17 witnessed a contraction in the employee base to just under 5.5 million.

To be sure, the data does not fully capture the upheaval in the Indian economy following the government’s demonetisation move of November 2016. For the current fiscal year, corporate employment figures will be available only after April 2018. And, the slowdown in the economy over the past few quarters could bring the numbers down further.

In fact, some estimates put the number of job losses at a whopping 1.5 million during the January-April 2017 period. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy's November 2017 estimates pegged the total employment numbers at 405 million, compared to 406.5 million, during the four months to January 2017.

As of March 2017, with over 387,000 employees on its rolls IT major Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) was India’s biggest job provider, followed by state-owned Coal India and State Bank of India (SBI), with 310,000 and 209,000 employees, respectively, while IT giants Infosys, Wipro, HCL Technologies and Tech Mahindra together employed another 539,000-odd people.

Effectively, therefore, just five IT companies account for 1.1 million employees, or more than one-fifth of India’s total corporate workforce. The data, however, does not include several other large IT employers, such as IBM and Accenture, which are not listed on Indian exchanges.

According to a September report by The New York Times, while IBM employs 130,000 people in India, others including Oracle, Dell, Cisco, Microsoft and Google, have a little over 85,000 Indians on their rolls.

Further analysis shows that sectors such as manufacturing, infrastructure, construction and engineering account for a majority job losses. Several bulk employers, including Coal India, Steel Authority of India Ltd and Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd, saw their headcounts go south, as did several private companies, including tea major Mcleod Russel, engineering and construction firm Larsen & Toubro and Tata Steel.

Interestingly, most IT majors and government banks saw their headcounts rise during the same period.

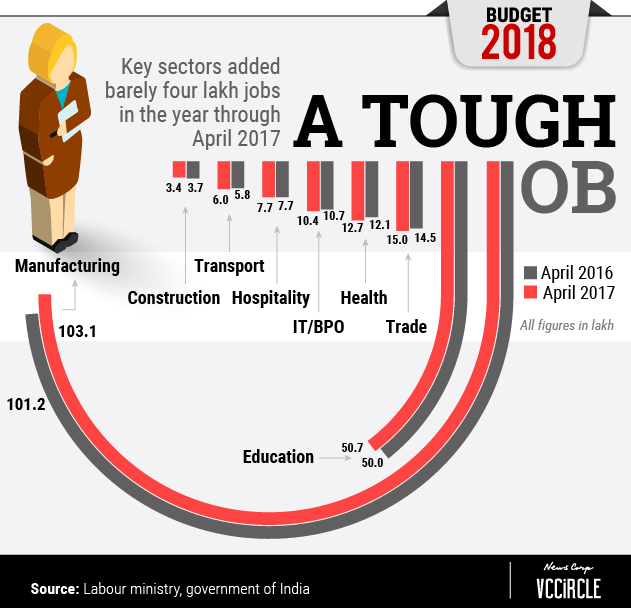

The other worry for the finance minister is that the government’s own data on jobs is, at best, patchy. The Labour Bureau, in fact, show a slightly rosy picture, but just about that. It says during 2016-17, India added just over 400,000 jobs to the 20.5 million employed across nine sectors, including manufacturing, construction, transport, hospitality, IT and healthcare.

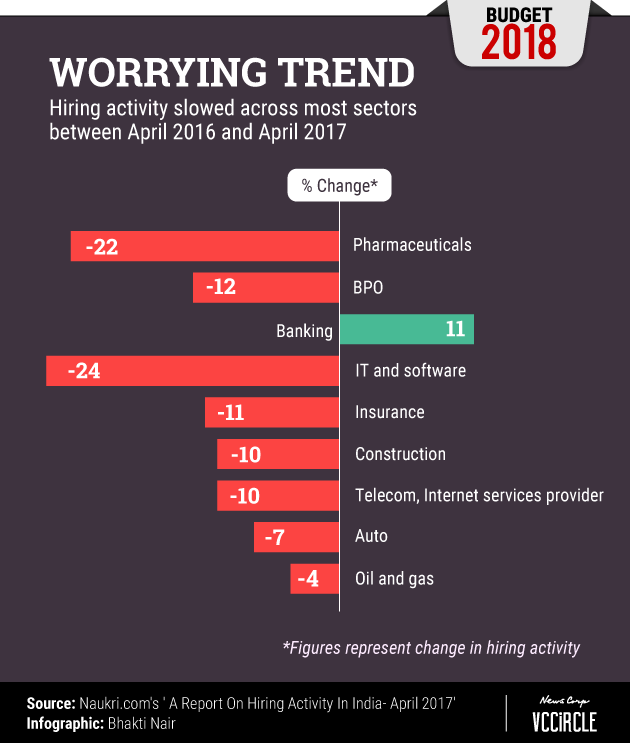

The data set, showing the uptick in employment, hides the fact that hiring activity had actually slowed across most marquee sectors during the period.

An April 2017 survey conducted by online recruiter Naukri.com showed that only the banking sector witnessed a rise in hiring. While IT-BPO and pharma were the worst hit, insurance, construction, telecom and auto also saw their respective work forces contract.

That said, India’s informal job sector, which had been severely impacted by demonetisation because of its dependence on cash transactions, continues to employ an overwhelming majority.

According to EY India’s chief policy advisor DK Srivastava, the finance minister is likely to focus on key sectors, including manufacturing, construction and infrastructure to boost the prospects of employment. “These sectors might be able to absorb both skilled and unskilled workers, and this might have a multiplier effect, and have a positive impact on the job numbers.â€

In 2015, just months after assuming office, the Modi government had launched the ‘Make in India’ programme to project the country as a manufacturing destination, as part of a bigger plan – to create employment and push exports. Thus far, the move seems to have achieved little.

In the 2017 budget, Jaitley had announced yet another ambitious project with SANKALP, a Rs 4,000 crore programme aimed at training and skilling 35 million youth. While we still do not know the impact of the project, as little current data is available, Jaitley is under pressure from India Inc. and lobby groups to reduce corporate tax rate, and live up to his promise of bringing it down to 25%.

But it is unlikely that the finance minister would have the legroom to reduce corporate taxes, given that the government may find it difficult to stay within its fiscal deficit target, said Srivastava.

Come 1 February, Jaitley must have a few tricks up his sleeves to address one of the major concerns that has been plaguing the country for a while – unemployment.