Finance minister Arun Jaitley will be presenting India’s first post-GST Budget – his fifth and the current dispensation’s last full budget – in barely three weeks. It will, in fact, be a major departure from previous editions, as it would not have to deal with indirect taxes, which have traditionally made up for a substantial chunk of budget proposals.

Finance minister Arun Jaitley will be presenting India’s first post-GST Budget – his fifth and the current dispensation’s last full budget – in barely three weeks. It will, in fact, be a major departure from previous editions, as it would not have to deal with indirect taxes, which have traditionally made up for a substantial chunk of budget proposals.

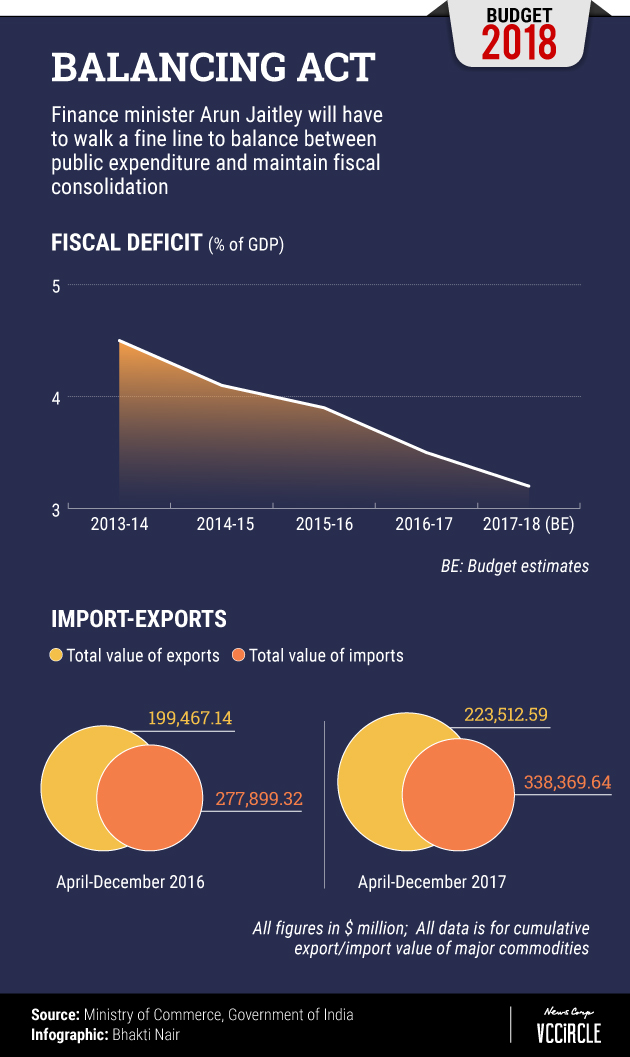

If the recent developments are anything to go by, Jaitley will have to walk a fine line, keeping in mind the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, while addressing the several challenges of an economy that is, at best, limping back to normalcy, following the twin reform blows in demonetisation and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax.

What’s more, the finance minister will, no doubt, have to focus on public spending and take significant steps to create more jobs. But that may be easier said than done, given the lower-than-normal indirect tax collections, ostensibly, owing to glitches in the GST Network, and an out of control fiscal deficit, which could shoot beyond the target of 3.2% of gross domestic product.

The government’s estimates is that the overall shortfall in tax revenue could be to the tune of Rs 55,000 crore – Rs 20,000 crore in direct taxes, and the rest in indirect taxes. This, despite the fact that direct tax collections for the first nine months of the fiscal year were up by over 18% to Rs 6.56 lakh crore, or two-thirds of the Rs 9.8 lakh crore estimated for 2017-18.

However, a section of experts sees the glass half full. “Higher personal advance-tax collection reflects (an) expansion of (the) tax base and (an) impact of demonetisation. This, probably allays fears of a slowdown in taxpayer base,” said Samir Kanabar, tax partner at EY India, in an emailed comment. “Also, the share of income-tax (at 67%) is significantly higher as compared to an average share of around 53% over the past four years.”

Kanabar’s views notwithstanding, the shortfall in tax collections prompted the Modi government to initially think of borrowing an additional Rs 50,000 crore to meet its spending requirements, sending the country’s bond markets in a tizzy.

However, the bond market recovered significantly during the course of the day, Wednesday, following a tweet by Subhash Chandra Garg, secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, Union Ministry of Finance. It said that the Centre had “reassessed additional borrowing requirements taking note of revenue receipts and expenditure pattern, to reduce additional borrowing from Rs 50,000 crore to Rs 20,000 crore”.

Given the initial announcement, bonds were trading at 18-month lows, and yields had surged as much as 17 basis points towards the end of December 2017.

Despite the tax shortfall, Jaitley could still give the Indian salaried middle class something to cheer about. Several experts feel the finance minister could increase the exemption limit for taxable income from Rs 2.5 lakh to Rs 3 lakh, besides introducing another tax slab. Last year, he had halved the tax on the Rs 2.5-5 lakh income band from 10% to 5%.

Besides, the latest growth estimates, too, should worry the finance minister. While the government’s earlier estimates for 2017-18 had pegged the growth of the Indian economy at 6.7%, the revised estimates put the figure at just about 6.5%. This, even as GDP growth during the July-September quarter was at 6.3%, the fastest this fiscal year.

Moreover, the rising spectre of retail inflation, which touched a 15-month high of 4.88% in November last, has put the central bank on the back foot. It is unlikely to bring down interest rates below the existing 6% anytime soon.

The other aspect that Jaitley will need to take stock off as he drafts his budget proposals is rising prices of global crude. In the first three years in office, Jaitley had immensely benefited from low crude prices, but the past year has seen the prices edge up significantly. Indian imports account for nearly 80% of its crude oil requirements.

Between 1 July 2017 and 14 January 2018, the import price of India’s crude basket went up from $46 a barrel to $76 a barrel, an increase of 63%. Although the slight appreciation in the rupee vis-a-vis the US dollar, did offset this equation slightly in favour of the Indian economy.

While crude price is still nowhere near its historic highs, it is unlikely to fall. Rising crude prices will not only up India’s import bill, but will also put pressure on its forex reserves, which had surged to a record high of $409.4 billion in the first week of January.

The finance minister will also have to work within certain limits, given that the government has yet again failed to meet its disinvestment targets for the year, despite 2017 being one of the best performing years in the history of the Indian stock market.

Of the Rs 46,500 crore targeted via divestment in public sector enterprises, the Centre has thus far netted just over Rs 32,321 crore. Similarly, of the Rs 15,000 crore it wanted to raise through the sale of strategic stakes, it has just managed to mop up Rs 4,153 crore.

However, through the listing of insurance companies, the government has exceeded its Rs 11,000 crore target by Rs 6,357 crore. Overall, it has raised Rs 53,833 crore, or 74% of the target amount, with just under three months to go.

Despite the Modi government’s efforts to hard sell India as an attractive investment destination, the country has not seen enough marquee foreign direct investment inflows that it could go to town with. Finally, it was compelled to soften the FDI norms with its recent announcement, allowing 100% FDI in single-brand retail. Besides, it has eased sourcing norms, which would effectively allow the likes of furniture retailer Ikea to set up shop in India.

Having said that, government data show that the current fiscal year has fared far better, year-on-year, with the first six months seeing FDI inflows of $25.35 billion, compared to $21.62 billion during the year-ago period.