Today is the 25th anniversary of the 1987 stock market crash that saw the worst ever one-day percentage decline on Wall Street. Worse even than during the Great Depression. It's a reminder that the market has had several October "crashes;" not only 1929 and 1987 but 1989, 1998, 2001 and 2007.

For some people this serves as a reminder to invest very, very cautiously. For others it is seen as market hiccups that present buying opportunities. For many it is an admonition to follow the investing advice of Mark Twain (although often attributed to Will Rogers) and pay more attention to the return of your money than the return on your money.

I've been investing for 30 years, and like most people I did it pretty badly. For the first 20 years the annual review with my Merrill Lynch stock broker sounded like "Kent, why is it I'm paying fees to you, yet would have done better if I simply bought the Dow Jones Industrial Average?" Across 20 years, almost every year, my "managed" account did more poorly than this collection of big, largely dull, corporations.

A decade ago I dropped my broker, changed my approach, and things have gone much, much better. Simply put I realized that everything I had been taught about investing, including my MBA, assured I would have, at best, returns no better than the overall market. If I used the collective wisdom, I was destined to perform no better than the collective market. Duh. And that is if I remained unemotional and disciplined - which I didn't assuring I would do worse than the collective market!

Remember, I am not a licensed financial advisor. Below are the insights upon which I based my new investing philosophy. First, the 4 myths that I think steered me wrong, and then the 1 thing that has produced above-average returns, consistently.

Myth 1 - Equities are Risky

Somewhere, somebody came up with a fancy notion that physical things - like buildings - are less risky than financial assets like equities in corporations. Every homeowner in America now knows this is untrue. As does anybody who owns a car, or tractor or even a strip mall or manufacturing plant. Markets shift, and land and buildings - or equipment - can lose value amazingly quickly in a globally competitive world.

The best thing about equities is they can adapt to markets. A smart CEO leading a smart company can change strategy, and investments, overnight. Flexible, adaptable supply chains and distribution channels reduce the risk of ownership, while creating ongoing value. So equities can be the least risky investment option, if you keep yourself flexible and invest in flexible companies.

Hand-in-glove with this is recognizing that the best equities are not steeped in physical assets. Lots of land, buildings and equipment locks-in the P&L costs, even though competitors can obsolete those assets very quickly. And costs remain locked-in even though competition drives down prices. So investing in companies with lots of "hard" assets is riskier than investing in companies where the value lies in intellectual capital and flexibility.

Myth 2 - Invest Only In What You Know

This is profoundly ridiculous. We are humans. There is infinitely more we don't know than what we do know. If we invest only in what we know we become horrifically non-diversified. And worse, just because we know something does not mean it is able to produce good returns - for anybody!

This was the mantra Warren Buffet used to turn down a chance to invest in Microsoft in 1980. Oops. Not that Berkshire Hathaway didn't find other investments, but that sure was an easy one Mr. Buffett missed.

To invest smartly I don't need to know a lot more than the really important trends. I don't have to know electrical engineering, software engineering or be an IT professional to understand that the desire to use digital mobile products, and networks, is growing. I don't have to be a bio-engineer to know that pharmaceutical solutions are coming very infrequently now, and the future is all in genetic developments and bio-engineered solutions. I don't have to be a retail expert to know that the market for on-line sales is growing at a double digit rate, while brick-and-mortar retail is becoming a no-growth, dog-eat-margin competitive world (with all those buildings - see Myth 1 again.) I don't have to be a utility expert to know that nobody wants a nuclear or coal plant nearby, so alternatives will be the long-term answer.

Investing in trends has a much, much higher probability of making good returns than investing in things that are not on major trends. Investing in what we know would leave most people broke; because lots of businesses have more competition than growth. Investing in businesses that are developing major trends puts the wind at your back, and puts time on your side for eventually making high returns.

Oh, and there are a lot fewer companies that invest in trends. So I don't have to study nearly as many to figure out which have the best investment options, solutions and leadership.

Myth 3 - Dividends Are Important to Valuation

Dividends (or stock buybacks) are the admission of management that they don't have anything high value into which they can invest, so they are giving me the money. But I am an investor. I don't need them to give me money, I am giving them money so they will invest it to earn a rate of return higher than I can get on my own. Dividends are the opposite of what I want.

High dividends are required of some investments - like Real Estate Investment Trusts - which must return a percentage of cash flow to investors. But for everyone else, dividends (or stock buybacks) are used to manipulate the stock price in the short-term, at the expense of long-term value creation.

To make better than average returns we should invest in companies that have so many high return investment opportunities (on major trends) that the company really, really needs the cash. We invest in the company, which is a conduit for investing in high-return projects. Not paying a dividend.

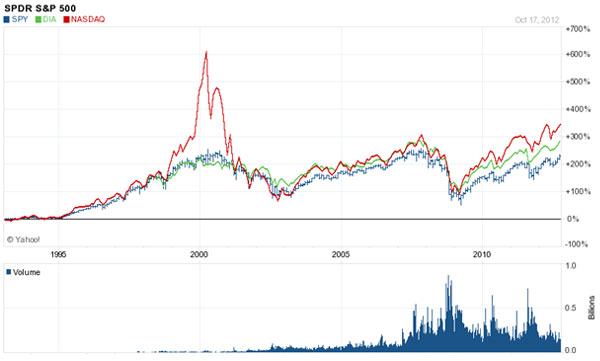

Myth 4 - Long Term Investors Do Best By Purchasing an Index (or Giant Portfolio)

Go back to my introductory paragraphs. Saying you do best by doing average isn't saying much, is it? And, honestly, average hasn't been that good the last decade. And index investing leaves you completely vulnerable to the kind of "crashes" leading to this article - something every investor would like to avoid. Nobody invests to win sometimes, and lose sometimes. You want to avoid crashes, and make good rates of return.

Investors want winners. And investing in an index means you own total dogs - companies that almost nobody thinks will ever be competitive again - like Sears, HP, GM, Research in Motion (RIM), Sprint, Nokia, etc. You would only do that if you really had no idea what you are doing.

If you are buying an index, perhaps you should reconsider investing in equities altogether, and instead go buy a new car. You aren't really investing, you are just buying a hodge-podge of stuff that has no relationship to trends or value cration. If you can't invest in winners, should you be an investor?

1 Truth - Growing Companies Create Value

Not all companies are great. Really. Actually, most are far from great, simply trying to get by, doing what they've always done and hoping, somehow, the world comes back around to what it was like when they had high returns. There is no reason to own those companies. Hope is not a good investment theory.

Some companies are magnificent manipulators. They are in so many markets you have no idea what they do, or where they do it, and it is impossible to figure out their markets or growth. They buy and sell businesses, constantly confusing investors (like Kraft and Abbott.) They use money to buy shares trying to manipulate the EPS and P/E multiple. But they don't grow, because their acquired revenues cost too much when bought, and have insufficient margin.

Most CEOs, especially if they have a background in finance, are experts at this game. Good for executive compensation, but not much good for investors. If the company looks like an acquisition whore, or is in confusing markets, and has little organic growth there is no reason to own it.

Companies that are developing major trends create growth. They generate internal projects which bring them more customers, higher share of wallet with their customers, and create new markets for new revenues where they have few, if any competition. By investing in trends they keep changing the marketplace, and the competition, giving them more opportunities to sell more, and generate higher margins.

Growing companies apply new technologies and new business practices to innovate new solutions solving new needs, and better solve old needs. They don't compete head-on in gladiator style, lowering margins as they desperately seek share while cutting costs that kills innovation. Instead they ferret out new solutions which give them a unique market proposition, and allow them to produce lots of cash for adding to my cash in order to invest in even more new market opportunities.

If you had used these 4 myths, and 1 truth, what would your investments have been like since the year 2000? Rather than an index, or a manufacturer like GE, you would have bought Apple and Google. Remember, if you want to make money as an investor it's not about how many equities you own, but rather owning equities that grow.

Growth hides a multitude of sins. If a company has high growth investors don't care about free lunches for workers, private company planes, free iPhones for employees or even the CEO's compensation. They aren't trying to figure out if some acquisition is accretive, or if the desired synergies are findable for lowering cost. None of that matters if there is ample growth.

What an investor should care about, more than anything else, is whether or not there are a slew of new projects in the pipeline to keep fueling the growth. And if those projects are pursuing major trends. Keep your eye on that prize, and you just might avoid any future market crashes while improving your investment returns.

(Adam hartung is the managing director at Spark Partners.)